Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Mazes in Python: Build, Visualize, Store, and Solve

If you’re up for a little challenge and would like to take your programming skills to the next level, then you’ve come to the right place! In this hands-on tutorial, you’ll practice object-oriented programming, among several other good practices, while building a cool maze solver project in Python.

From reading a maze from a binary file, to visualizing it using scalable vector graphics (SVG), to finding the shortest path from the entrance to the exit, you’ll go step by step through the guided process of building a complete and working project.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn how to:

- Use an object-oriented approach to represent the maze in memory

- Define a specialized binary file format to store the maze on disk

- Transform the maze into a traversable weighted graph

- Use graph search algorithms in the NetworkX library to find the solution

- Visualize the maze and its solution using scalable vector graphics (SVG)

Click the link below to download the complete source code for this project, along with the supporting materials, which include a few sample mazes:

Free Download: Click here to download the source code and supporting materials that you’ll use to build a maze solver in Python.

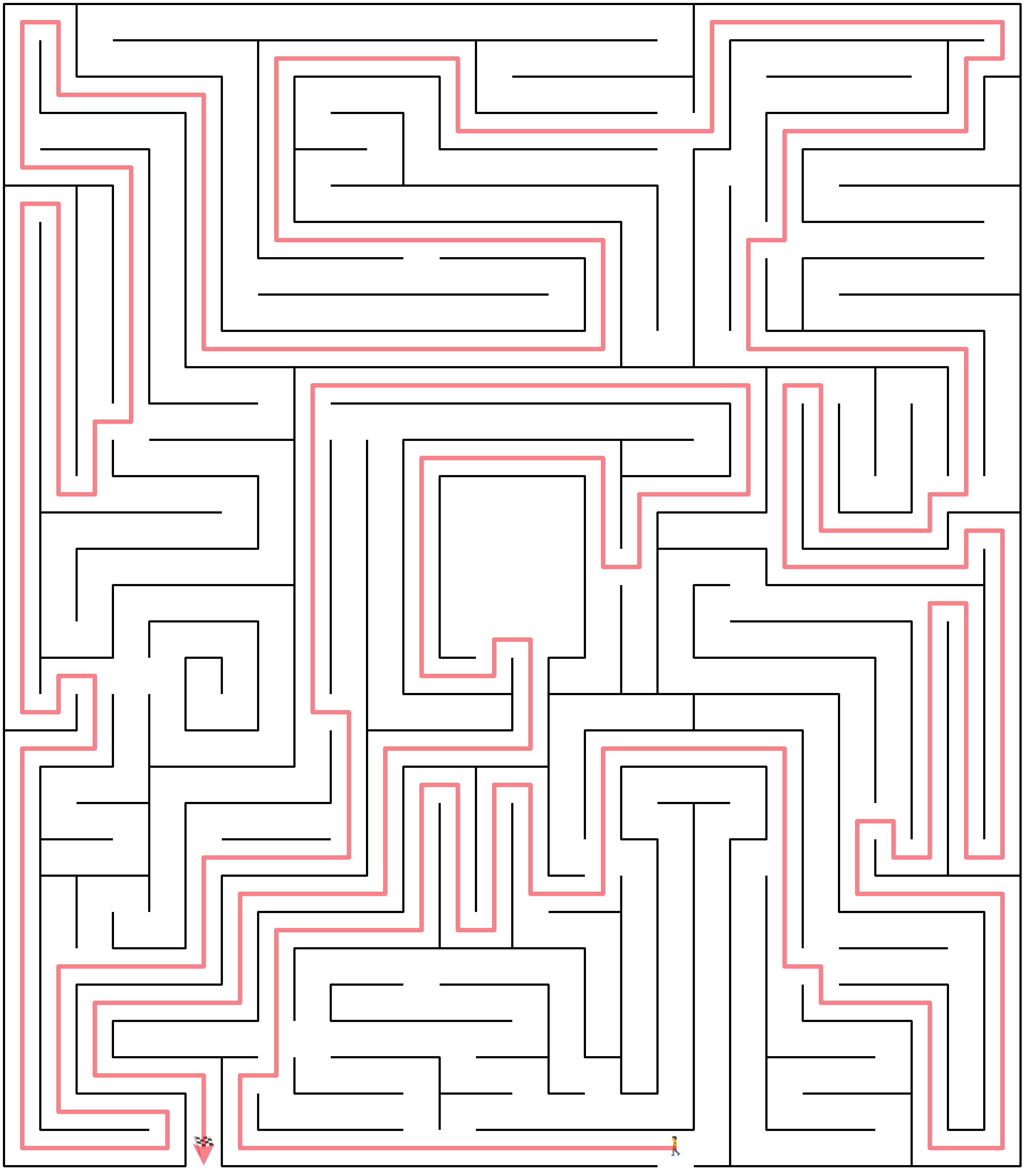

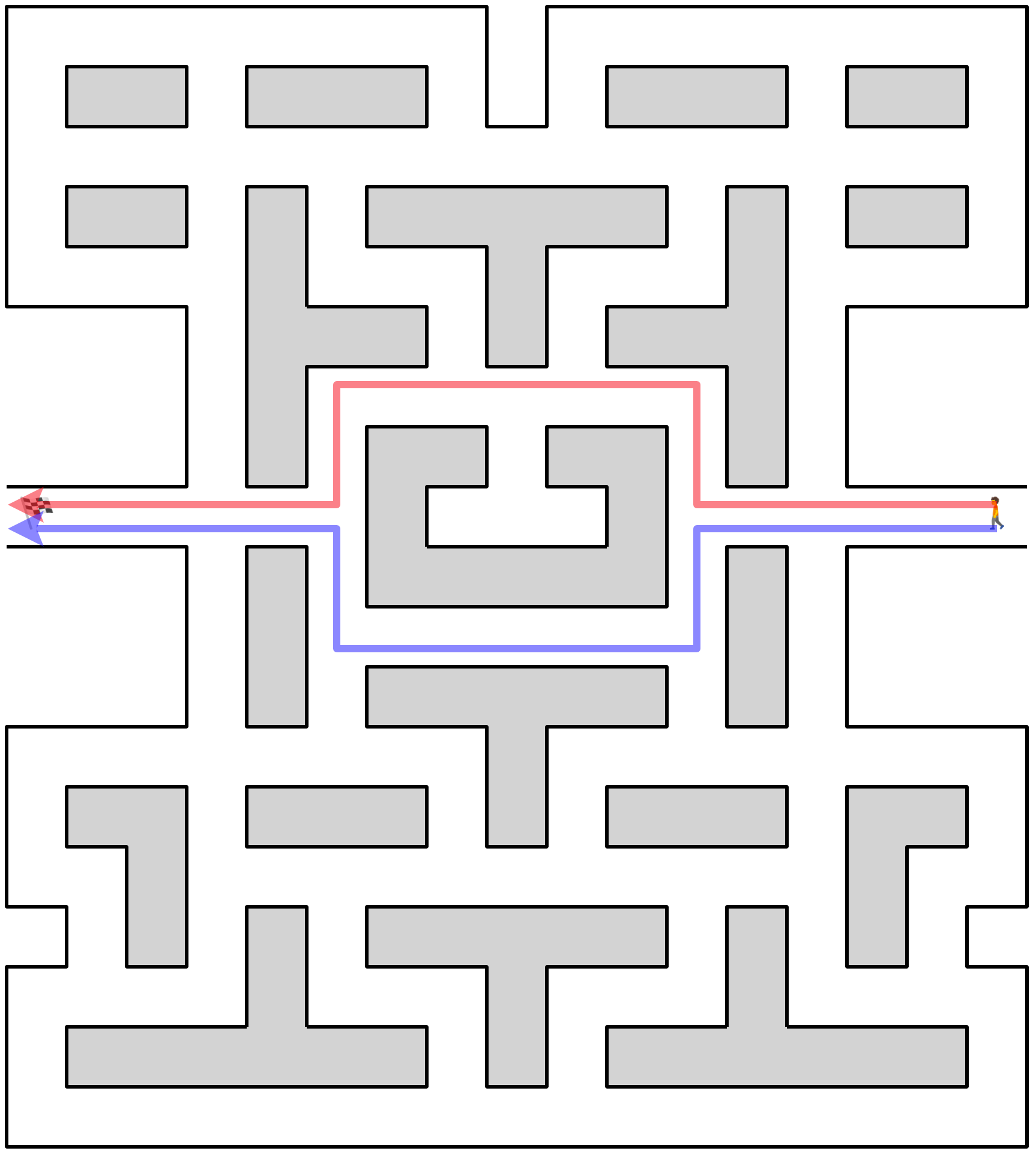

Demo: Python Maze Solver

At the end of this tutorial, you’ll have a command-line maze solver that can load your maze from a binary file and show its solution in the web browser:

You’ll learn how to build your own mazes like this from scratch and save them on disk. In the meantime, feel free to grab one of the sample mazes from the supporting materials. Now, get ready to dive in!

Project Overview

Take a glimpse at the expected file structure of your project. Once finished, your project’s file and directory tree will look as follows:

maze-solver/

│

├── mazes/

│ ├── labyrinth.maze

│ ├── miniature.maze

│ └── pacman.maze

│

├── src/

│ │

│ └── maze_solver/

│ │

│ ├── graphs/

│ │ ├── __init__.py

│ │ ├── converter.py

│ │ └── solver.py

│ │

│ ├── models/

│ │ ├── __init__.py

│ │ ├── border.py

│ │ ├── edge.py

│ │ ├── maze.py

│ │ ├── role.py

│ │ ├── solution.py

│ │ └── square.py

│ │

│ ├── persistence/

│ │ ├── __init__.py

│ │ ├── file_format.py

│ │ └── serializer.py

│ │

│ ├── view/

│ │ ├── __init__.py

│ │ ├── decomposer.py

│ │ ├── primitives.py

│ │ └── renderer.py

│ │

│ ├── __init__.py

│ └── __main__.py

│

├── pyproject.toml

└── requirements.txt

Yes, that’s a lot of files, but don’t worry! Most of them are fairly short, and some contain only a few lines of code. This helps keep things organized and makes the individual pieces reusable, letting you compose them in new ways. Such granularity also plays an important role in Python projects with larger codebases by avoiding the notorious circular dependency error that you might encounter if various parts of the code were in one big file.

The mazes/ subfolder is home to a few binary files with sample data that you’re going to use in this tutorial. You can get these files, along with the final source code and snapshots of the individual steps, by downloading the supporting materials:

Free Download: Click here to download the source code and supporting materials that you’ll use to build a maze solver in Python.

The src/ subfolder contains your Python modules and packages for the maze solver project. The maze_solver package consists of several subpackages that group logically related code fragments, including:

graphs: The traversal and conversion of the maze to a graph representationmodels: The building blocks of the maze and its solutionpersistence: A custom binary file format for persistent maze storageview: The visualization of the graph with scalable vector graphics

You’ll also find the special __main__.py file, which makes the enclosing package runnable so that you can execute it directly from the command line using Python’s -m option:

$ python -m maze_solver /path/to/sample.maze

When launched like this, the package reads the specified file with your maze. After solving the maze, it renders the solution into an SVG format embedded in a temporary HTML file. The file gets automatically opened in your default web browser. You can also run the same Python code using a shortcut command:

$ solve /path/to/sample.maze

It’ll work as long the solve command isn’t already taken or aliased by another program.

Finally, pyproject.toml provides your project’s configuration, metadata, and dependencies defined in the TOML format. The project only depends on one external library, which you’ll use to find the shortest path in the maze represented as a graph.

Next up, you’ll review a list of relevant resources that might become your savior in case you get stuck at any point. Also, remember the supporting materials, which contain a snapshot of each finished step. Along the way, you can compare your progress to the relevant step to ensure that you’re on the right track.

Prerequisites

This tutorial will best suit intermediate Python developers who’d like to practice object-oriented programming (OOP) while building a cool project. Throughout this tutorial, you’ll be using several neat features of modern Python, so make sure you’re on Python 3.10 or later. Also, it might be worth brushing up on the following topics before you dive in:

- Assignment expressions

- Bitwise operators

- Class methods

- Data classes

- Enum

typing.NamedTuple- Structural pattern matching

- Type hints

Note that you don’t need to be an expert in any of these areas to follow along with the tutorial, as it’ll guide you through the steps involved. In fact, a key aspect of your learning experience will be seeing these features in a practical context.

With that out of the way, you can move on to your project!

Step 1: Lay the Groundwork for the Project

The first step to writing any code starts on paper. Therefore, you’ll now take a step back to figure out what problem you’re solving and how you’re going to approach it. You’ll begin by narrowing down the design requirements for your maze.

Define the Problem Constraints

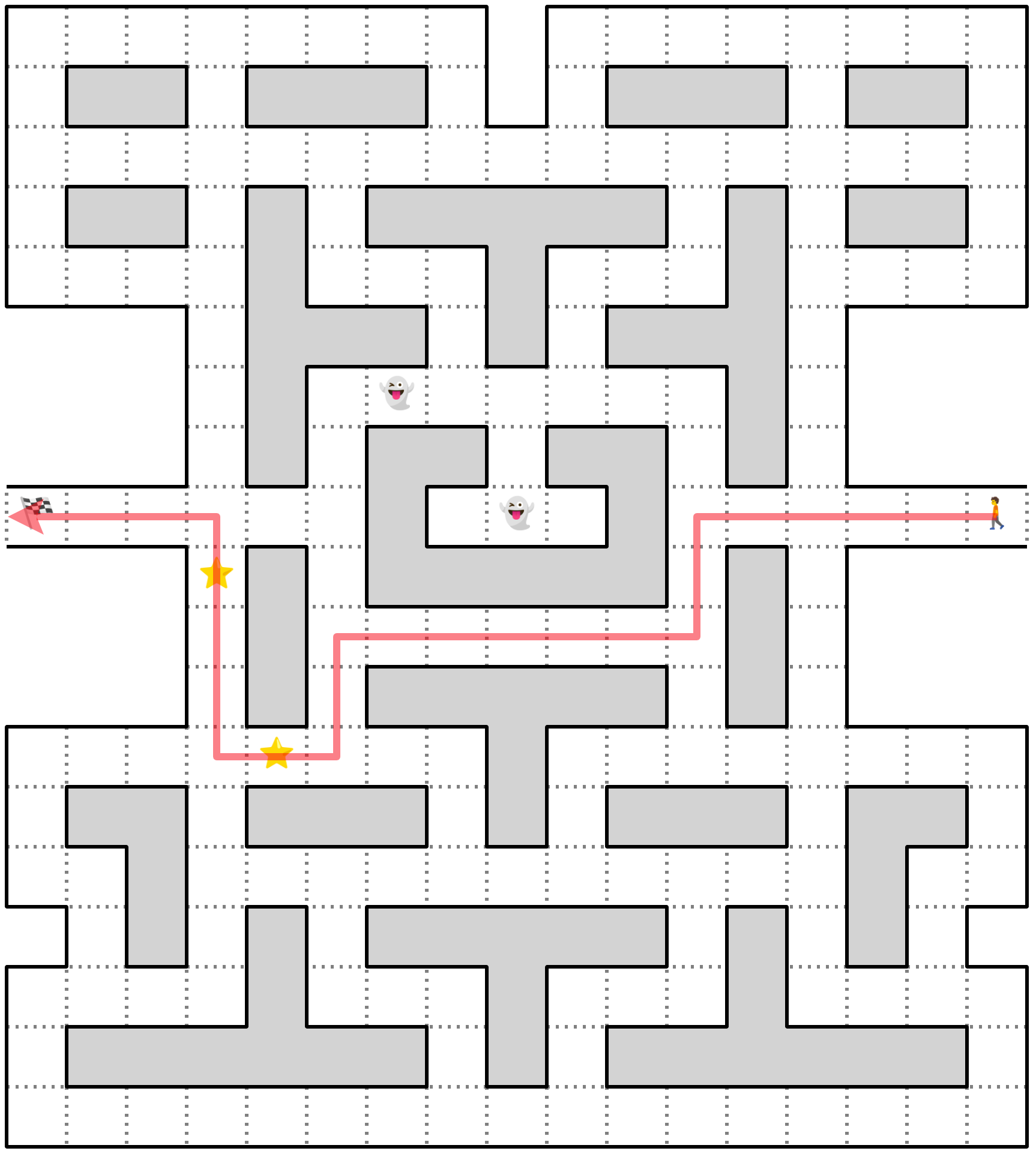

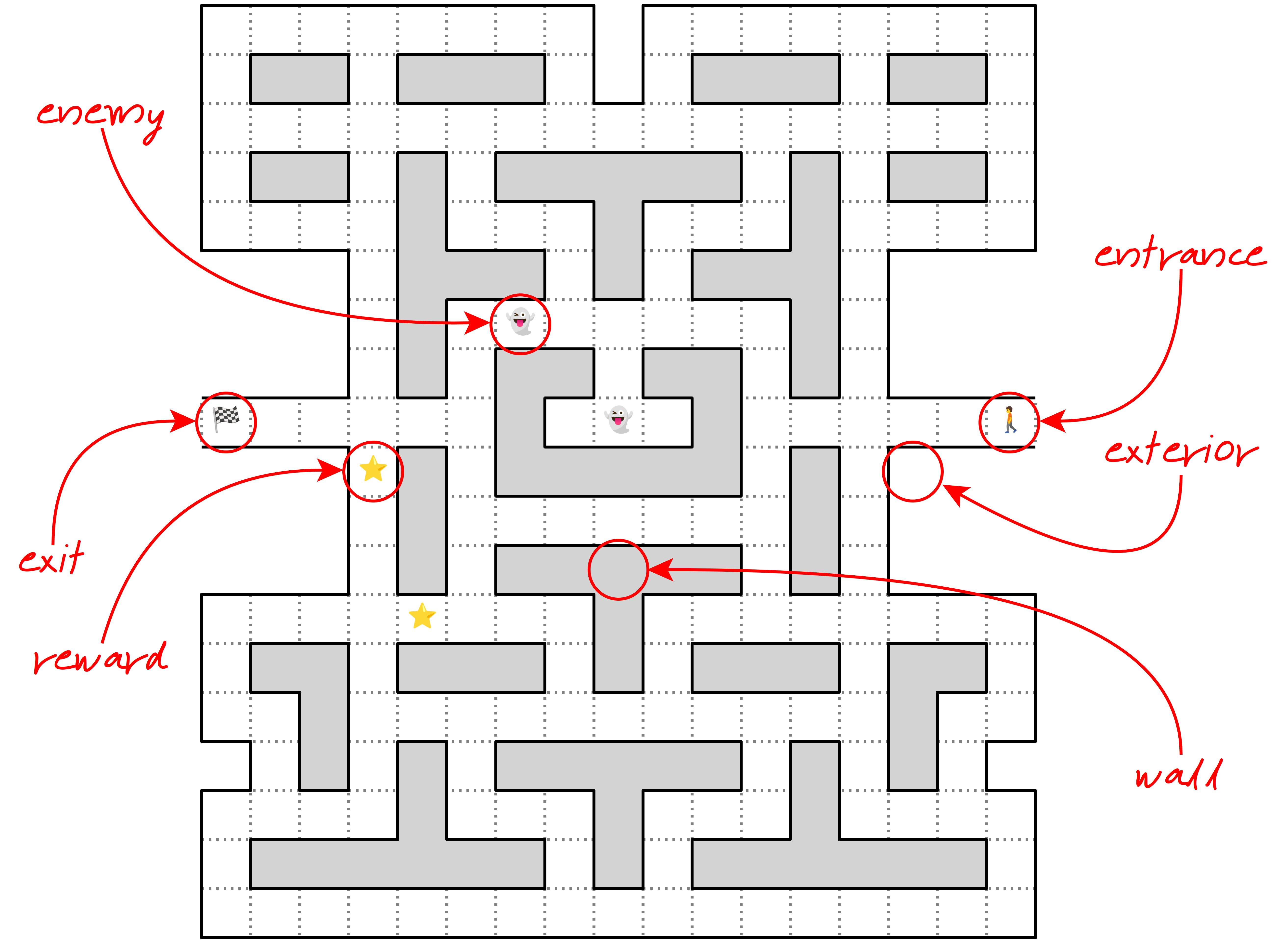

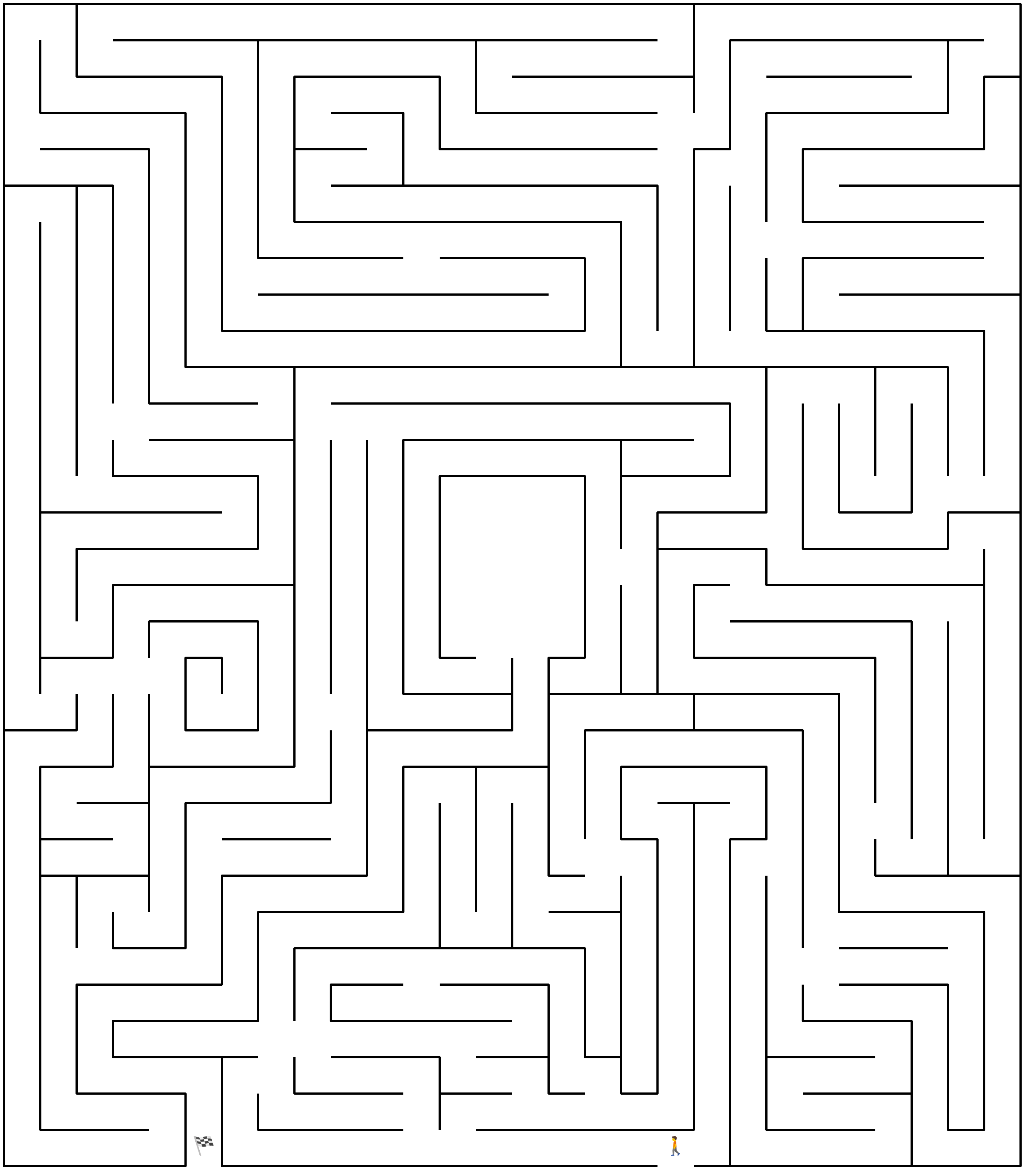

Mazes come in different shapes and forms, but you’ll concentrate on one kind that you’d find in a typical maze-puzzle video game from the early 1980s, like Boulder Dash or Sokoban. For example, the following maze was inspired by the classic Pac-Man game:

This maze is enclosed in a rectangle comprising a grid of square cells that form passages along straight lines. Therefore, paths in your maze will only be vertical or horizontal rather than diagonal or circular, for example, and each cell will be one unit wide. This will become important for calculating and comparing the distances later.

Note: You can give your maze any shape by surrounding it with empty squares marked as exterior to form an open space. However, you might want to align the maze’s edges with the enclosing rectangle to save some memory.

An additional restriction that you’ll impose on your maze is that it must have exactly one entrance and exactly one exit, both of which should occupy distinct cells. A few alternative paths can connect them, including paths with cycles that lead back to a place you’ve already visited.

Solving the maze means finding a path leading from the entrance to the exit. Each solution should include acyclic paths. In other words, a single path location should only be traversed once without backtracking. You also want to consider only the shortest paths while disregarding less optimal, meandering ones. However, defining the shortest distance is subject to interpretation, as you’ll find out later in this tutorial.

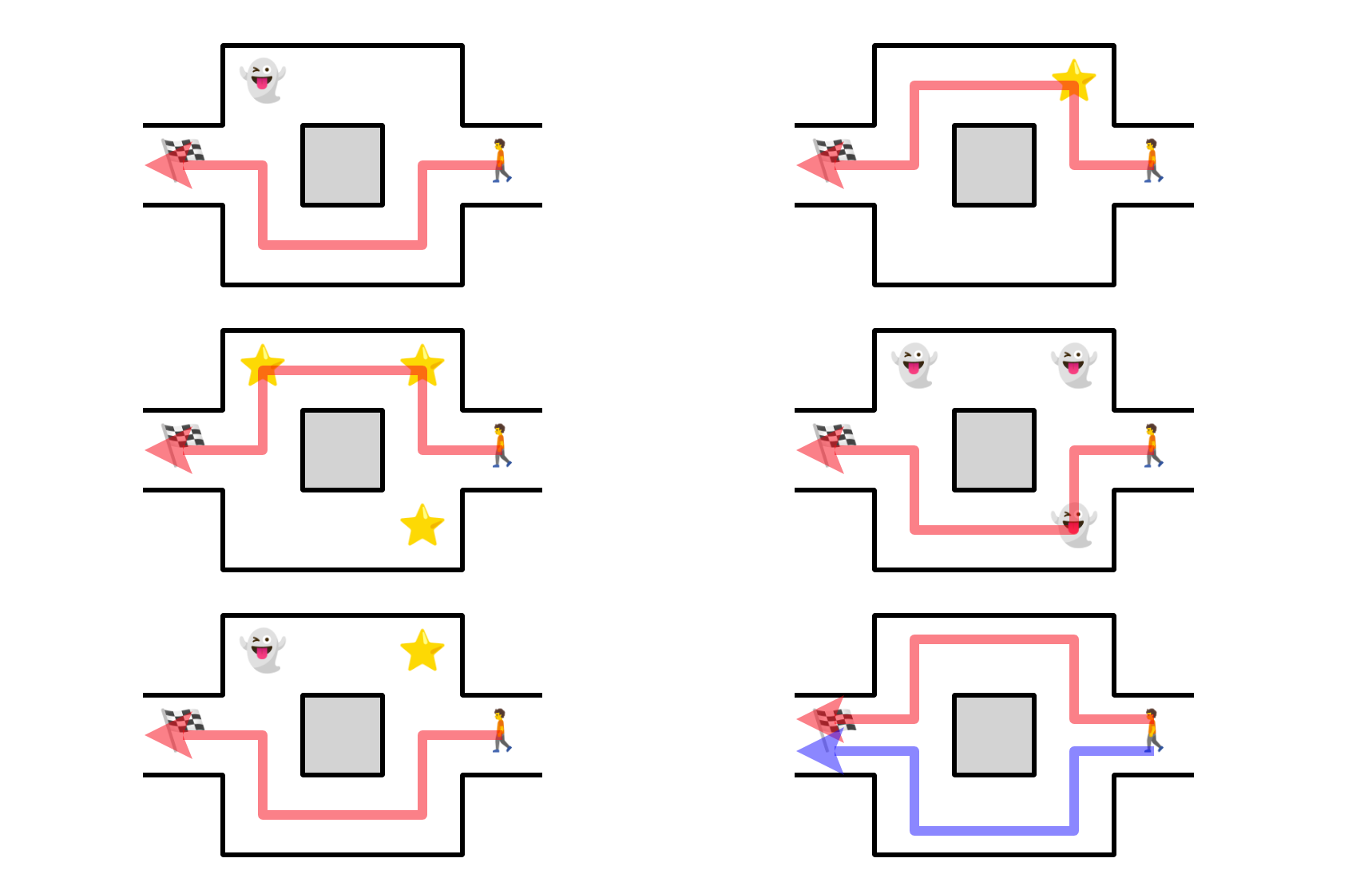

Later, you’ll introduce enemies and rewards to the maze so that your hypothetical player can collect extra points and avoid obstacles. But how do you actually find the way out of the maze?

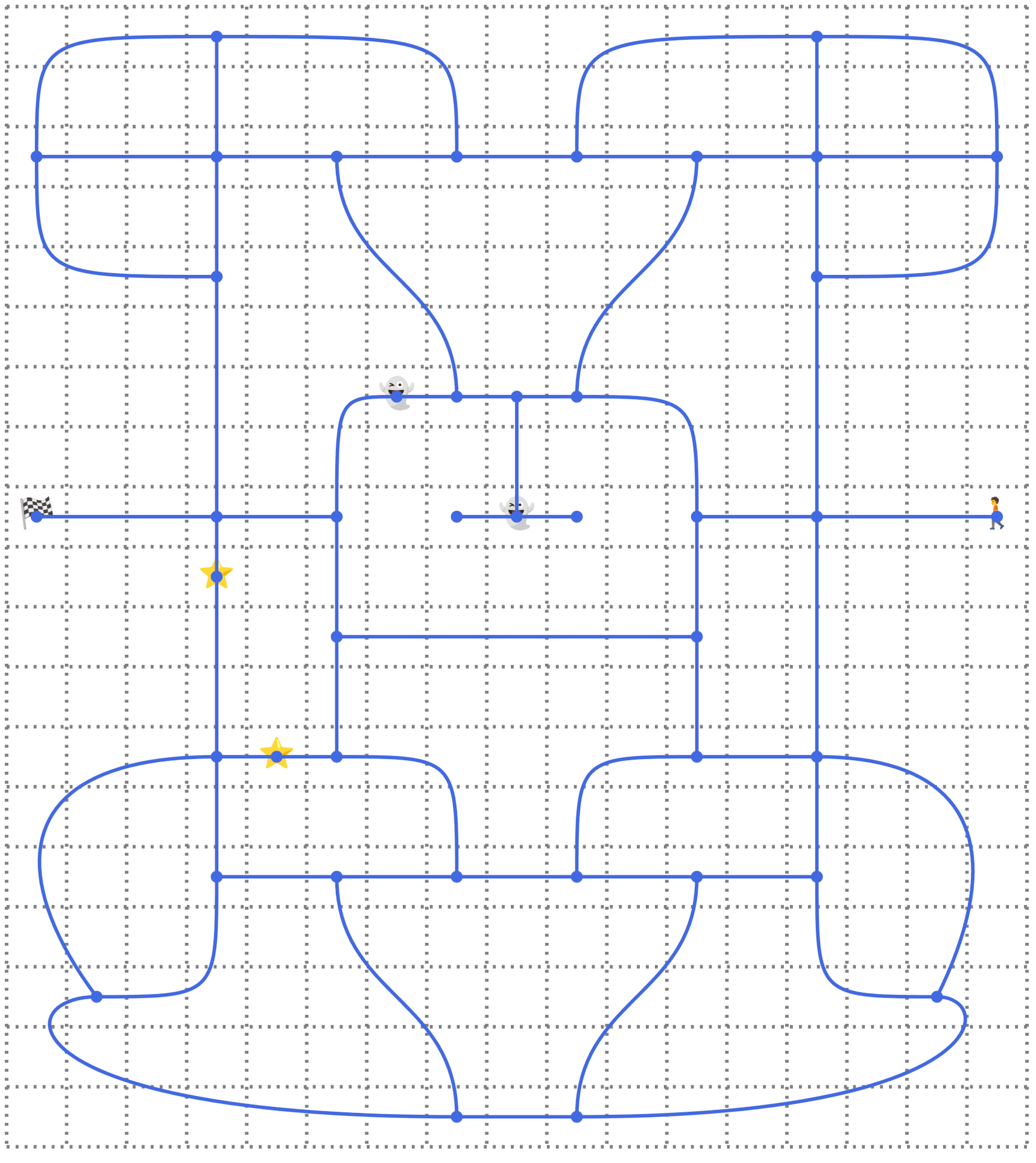

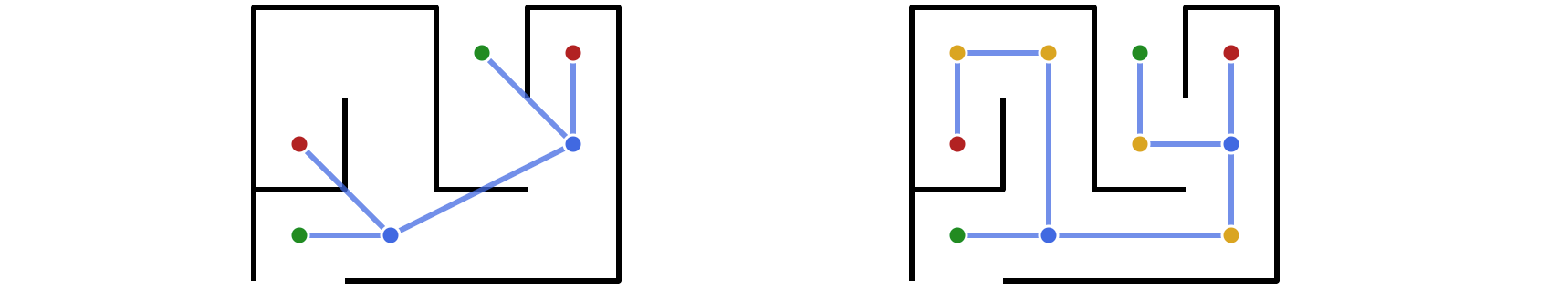

Well, mazes are a perfect example of graph theory in action. As it turns out, you can represent your maze with an undirected graph consisting of nodes and edges connecting them. Each node or vertex is where two or more paths intersect, while edges are the connections between those intersections:

Apart from nodes representing the intersections and dead ends in the maze, there are a few extra nodes in the graph above that capture the presence of enemies and rewards. By associating numeric weights with edges that pass through them, you can influence the cost of the given connection. Later, you’ll add nodes for corners to make plotting the path from the entrance to the exit a tad bit easier.

Note: Strictly speaking, the graph corresponding to a maze can be a more specialized type known as a multigraph when it has two or more parallel edges that connect neighboring nodes.

It’s worth noting that you can draw the same graph in different ways without changing its underlying structure. For example, you could draw all edges as straight lines, let them cross each other, or arrange the nodes in a certain pattern.

Mathematically, a graph is nothing more than a set of nodes and edges, which you can lay out in any order and locations you like. Therefore, transforming the maze into a graph is an irreversible process resulting in losing some information about its visual features. At the same time, a graph is a remarkably convenient representation for finding the shortest path in the maze.

In this tutorial, you won’t be implementing any graph traversal algorithms, such as the depth-first search (DFS), breadth-first search (BFS), or Dijkstra’s algorithm for finding the shortest path. Instead, you’ll leverage the excellent NetworkX library, which already implements these and more algorithms, to do the heavy lifting for you.

Now that you’ve clarified the problem at hand, you can start thinking about how to approach it from a technical perspective. It’s time to lay the groundwork for some Python code!

Scaffold the Project Structure

Use your favorite code editor or a cloud-based IDE to create a new Python project while specifying an isolated virtual environment for its dependencies. The minimum interpreter version required for this project is Python 3.10 due to a few syntactic constructs introduced in that release, which you’ll be using. If you can, consider switching to a more recent release for better performance and other improvements.

Note: You may use pyenv to manage multiple Python versions on your computer.

Once you have the project set up in your editor, scaffold the initial folder structure with these two nested Python packages, both of which should be empty at the moment:

maze-solver/

│

├── src/

│ │

│ └── maze_solver/

│ │

│ ├── models/

│ │ └── __init__.py

│ │

│ └── __init__.py

│

└── pyproject.toml

By placing the project’s root package under the src/ subfolder, you follow the so-called src layout convention for organizing files in a project. Note that the pyproject.toml file should live outside of the src/ subfolder.

The alternative is a flat layout with all files in the same folder. You can read about their differences in the official Python Packaging User Guide. In a nutshell, the src layout is preferred for larger projects because it allows you to better separate the project code from other files, such as tests.

While the project’s name is maze-solver with a hyphen (-), you named the corresponding Python package using an underscore character (_) to form a valid Python identifier, which follows the same rules as variable names. The rules for naming a Python project, or a distribution package in slightly more technical terms, are more liberal. If you’re curious enough, you can check PEP 508 to find the regular expression that validates these names.

To install your project in an active virtual environment, you’ll need to specify the minimum required configuration in the TOML file, such as the name and version of your project. Go ahead and open your pyproject.toml file now, and then paste the following content into it:

# pyproject.toml

[build-system]

requires = ["setuptools>=64.0.0", "wheel"]

build-backend = "setuptools.build_meta"

[project]

name = "maze-solver"

version = "1.0.0"

It’s a pretty standard configuration and a good starting point for most Python projects and libraries. Note that you don’t have to explicitly state what folder layout your project is following because the build tools like setuptools will automatically find your Python source code.

If you’re planning to publish your package on PyPI, then you should pick a globally unique name that won’t conflict with an existing Python distribution package. Otherwise, you have a fair amount of freedom in choosing your project name.

After you’ve saved your changes in the pyproject.toml file, you can install maze-solver with pip by running the following command from the root directory of your project:

(venv) $ python -m pip install --editable .

During the development of a src-layout project, it’s advisable to use the --editable flag or its -e alias to ensure that any changes you make to your code are immediately reflected in the virtual environment. Otherwise, you’d have to manually reinstall the package each time you edit the code.

Note: If you run into an error about not being able to install the directory in editable mode due to a missing setup.py or setup.cfg file, then you may need to upgrade pip itself:

(venv) $ python -m pip install --upgrade pip

Projects based on pyproject.toml support editable installs through PEP 660, which was implemented in pip starting from version 21.3.

To confirm that you’ve successfully installed the maze_solver package in your virtual environment, head over to the interactive Python REPL and try importing the package:

>>> import maze_solver

If everything works fine, then you shouldn’t see any output or error messages after running the line of code above. Otherwise, you’ll immediately get a ModuleNotFoundError.

Great! With the scaffolded Python project in place, you can now proceed to coding an object-oriented representation of the maze.

Step 2: Represent the Maze Using an Object-Oriented Approach

At this point, you know what kind of maze you’ll be solving and have a good idea of the best data structure to represent it with.

In this step, you’ll use a top-down approach to conceptually decompose the maze into a set of basic elements. One by one, you’ll implement those elements as objects and combine them to represent the complete maze. By the end of this step, you’ll be able to build any maze you like, including virtual replicas of real-world hedge mazes, maize mazes, or even ice mazes that can be found in amusement parks around the world!

Identify the Building Blocks of the Maze

For the purpose of this tutorial, you can think of the maze as a rectangular grid of uniform squares arranged in rows and columns. Each square has the same width and height and a piece of border around it. Squares can additionally play specific roles in the maze to make it more interesting. For example, some of them can represent obstacles like walls or enemies, while others can represent rewards.

To avoid tight coupling between your building blocks, which could manifest itself through the circular import error mentioned earlier, you’re going to put the individual classes in separate files. Go ahead and create the following four Python module placeholders in the models package:

maze-solver/

│

├── src/

│ │

│ └── maze_solver/

│ │

│ ├── models/

│ │ ├── __init__.py

│ │ ├── border.py

│ │ ├── maze.py

│ │ ├── role.py

│ │ └── square.py

│ │

│ └── __init__.py

│

└── pyproject.toml

Each empty file corresponds to one of the building blocks you just identified. Over the remaining sections, you’ll fill them with the necessary code. You’ll begin by defining the available roles of a square in the maze.

Assign Roles to Squares

Most squares won’t have any particular role in the maze. However, at least two of them must be marked as the entrance and the exit, respectively. They will tell the pathfinding algorithm where to start and finish its journey. Some other squares can be marked as obstacles like walls, enemies, or the exterior, which you can’t cross. Finally, a few squares can contain rewards, like bonus points or power-ups that may influence the path.

Here’s that same maze you saw before, but with a few of its squares annotated so that you can get a better idea of their different roles:

All in all, there are six unique roles you can assign to the squares in any given maze:

- Enemy

- Entrance

- Exit

- Exterior

- Reward

- Wall

A role is optional, so the square doesn’t have any by default. On the other hand, when a square already has some role, then it can’t have another role at the same time. For instance, you mustn’t place a reward and an enemy on the same square. Note this is just an arbitrary constraint on the problem to make it easier to solve, which doesn’t hold true for all mazes in general.

The most appropriate data type for representing square roles in Python, which can enforce such rules, is an Enum. It lets you choose at most one role from a fixed set of mutually exclusive values.

Open the role module in your project and define the following class in it:

# models/role.py

from enum import IntEnum, auto

class Role(IntEnum):

ENEMY = auto()

ENTRANCE = auto()

EXIT = auto()

EXTERIOR = auto()

REWARD = auto()

WALL = auto()

Your class extends the enum.IntEnum base class from the standard library, which provides special semantics for its instances. There are currently only six such instances, which have unique identities, called members of the enumeration. You usually write their names in uppercase to indicate that they behave like constants, but unlike regular constants, they share a common namespace.

By calling enum.auto(), you give each member the next numeric value in turn.

At this point, it doesn’t make much difference whether you extend enum.IntEnum or the more basic enum.Enum type. However, the benefit of using the former will become apparent when you start implementing a custom file format in step 4 to save your mazes on disk in binary form.

Because enum.IntEnum is also a subclass of int, as the name implies, you can treat your Role members as numbers:

>>> from maze_solver.models.role import Role

>>> Role.ENEMY

<Role.ENEMY: 1>

>>> Role.ENEMY.value

1

>>> Role.ENEMY + 42

43

Even though regular enumerations defined with enum.Enum would have identical numeric values, they don’t support operators associated with math expressions, such as the plus operator (+). You’ll use this feature to combine roles with other information about the square.

Remember that a role is optional. Therefore, you could use a special null value to indicate the lack of a role in a given square. In Python, that null value is the built-in None. However, empty values can be problematic because they force you to add a conditional branch to your code that’ll handle the missing value whenever you want to access an attribute. If you forget to check for a None value, then you may get an error.

Fortunately, in the object-oriented world, there’s a convenient design pattern called the null object pattern, which can help you avoid this issue. In short, the pattern instructs you to stop using None in favor of dedicated null objects representing the missing value of the associated types. Generally, each attribute type should have its own null object that can implement the desired interface with some default behavior, such as a no-op.

To follow this pattern in your Role enumeration, specify an additional member that’ll serve as the null object:

# models/role.py

from enum import IntEnum, auto

class Role(IntEnum):

NONE = 0

ENEMY = auto()

ENTRANCE = auto()

EXIT = auto()

EXTERIOR = auto()

REWARD = auto()

WALL = auto()

Because enum.auto() starts enumerating your members from one and then picks up the value of the previous member, the default values may not always be desirable. If you’d like to change them, then you can explicitly set an arbitrary value for some members, like on the highlighted line in the code snippet above. In this case, using zero as the null object’s value feels more appropriate than one.

Now, you can assign a Role instance to all of the squares, even if some of them don’t play an inherent role in your maze. That way, you can treat the squares in a uniform manner, which will greatly simplify your future code.

So far, you’ve defined roles for the squares in the maze. Its next building block is the border around each square, which will let you give them a visual appearance and sense of location.

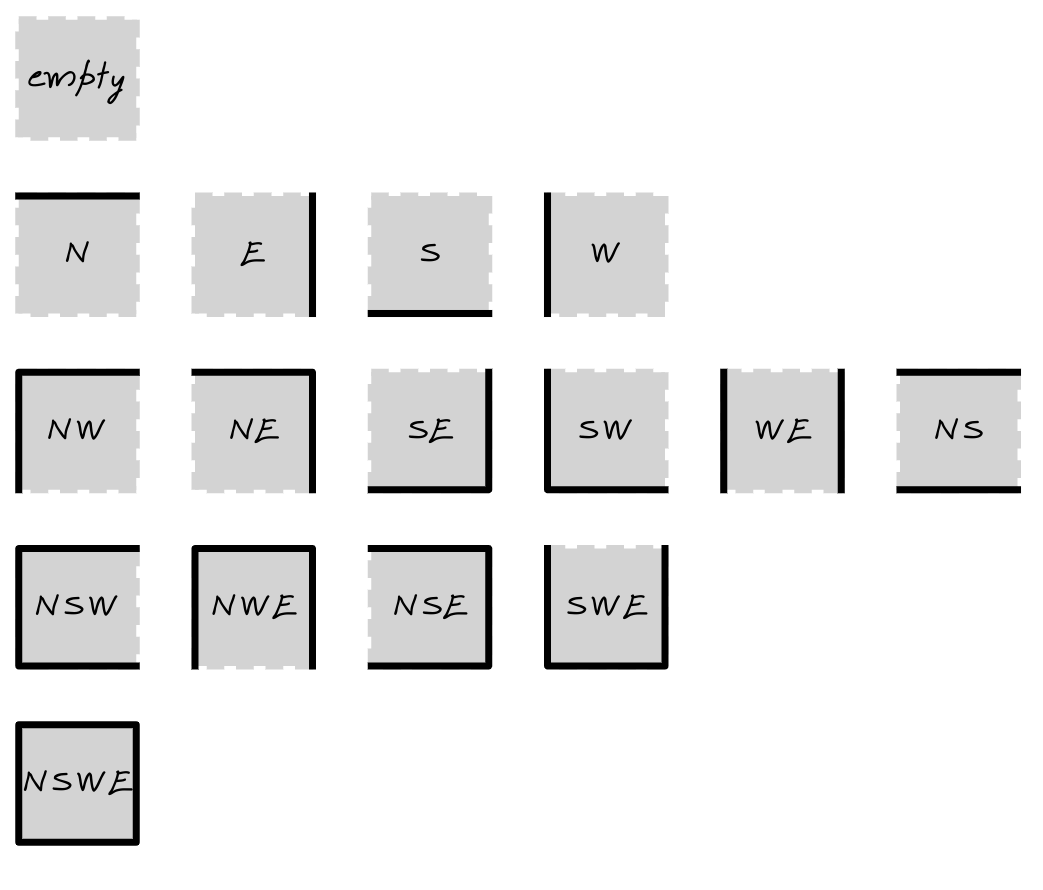

Create Border Patterns

Each square can have between zero and four sides painted along the main compass directions—that is, north (N), south (S), east (E), and west (W). When you do the math, then you’ll find out that there are sixteen combinations of unique side patterns in total, ranging from an empty square to one with all four sides painted:

There’s one empty square, four squares with only one side, six squares with two sides, four squares with three sides, and one square with all four sides. Now, you can build almost any maze pattern with these tiles by connecting them like a jigsaw puzzle!

To compactly represent a border pattern around a square with just a single number, consider using a bit field, which maps each of the four sides to a specific binary digit. Extracting information from such a number usually requires the use of bitwise operators, which aren’t very common in Python. However, in this tutorial, you’ll use a handy shortcut from the standard library, which hides the tedious details.

Because there are four sides, you must allocate four bits that you can individually turn on or off depending on whether or not there’s a border on that side. When you convert the corresponding bit string into a decimal number, you’ll get the unambiguous representation of one of the border patterns:

| Border Sides | Bit String | Bit Count | Decimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 00002 | 0 | 0 | |

| N | 00012 | 1 | 1 |

| S | 00102 | 1 | 2 |

| W | 01002 | 1 | 4 |

| E | 10002 | 1 | 8 |

| NS | 00112 | 2 | 3 |

| NW | 01012 | 2 | 5 |

| NE | 10012 | 2 | 9 |

| SW | 01102 | 2 | 6 |

| SE | 10102 | 2 | 10 |

| WE | 11002 | 2 | 12 |

| NSW | 01112 | 3 | 7 |

| NSE | 10112 | 3 | 11 |

| NWE | 11012 | 3 | 13 |

| SWE | 11102 | 3 | 14 |

| NSWE | 11112 | 4 | 15 |

As you can see, each border pattern is represented with a decimal number ranging from zero to fifteen. You can check which sides are included in the border by looking at the binary representation of the number and reading the corresponding bits. If a bit is set to one, then you’ll know that you should paint that side of the border.

The bit count, or the number of ones in the bit string, reflects the number of sides in the border. Additionally, it carries some useful information about the type of square.

For example, you can recognize a dead end by detecting precisely three sides of the border, leaving only one end to connect with other squares. Fewer than two sides may indicate a potential intersection of paths in the maze if the square isn’t a wall or part of the exterior. Specifically, a T-shaped intersection will have one side, while a four-way intersection will have none.

Detecting a corner is a bit more tricky because it requires you to compare the border against one of the four specific patterns, even though they all have exactly two sides:

- NW

- NE

- SW

- SE

This helps eliminate the other two border patterns, NS and WE, that also have two sides but aren’t corners. Their sides run in parallel instead of meeting at a corner.

Okay, now that you know what makes a square border, how do you define it in Python?

In short, you’ll use the Enum data type again, but with a slight twist. This time around, you’ll extend the enum.IntFlag base class, which is an even more specific enumeration type that implements the bit field logic. You’ll give more common names to your enum members instead of using the compass directions. Add this code to the border module:

# models/border.py

from enum import IntFlag, auto

class Border(IntFlag):

EMPTY = 0

TOP = auto()

BOTTOM = auto()

LEFT = auto()

RIGHT = auto()

You override the default value of Border.EMPTY with a zero to indicate the absence of border sides.

This class resembles the Role enumeration that you defined in the previous section, but IntFlag allows you to do much more with its members. Rather than being a mutually exclusive choice of one member, the Border enumeration lets you combine any number of its members to create a composite value. For example, to define a closed border, you’d combine all four sides using the bitwise OR (|) operator:

>>> from maze_solver.models.border import Border

>>> border = Border.TOP | Border.BOTTOM | Border.RIGHT | Border.LEFT

>>> border

<Border.TOP|BOTTOM|LEFT|RIGHT: 15>

>>> border.name

'TOP|BOTTOM|LEFT|RIGHT'

>>> border.value

15

The .name and .value attributes of the resulting border are calculated dynamically based on the combination of its sides.

Note that the order of the individual sides doesn’t matter when you define a composite bit field:

>>> Border.TOP | Border.BOTTOM

<Border.TOP|BOTTOM: 3>

>>> Border.BOTTOM | Border.TOP

<Border.TOP|BOTTOM: 3>

Underneath, it’s a numeric value resulting from turning on the specific bits. Python will always show a consistent text representation of that value, determined by the order of your members in the class definition.

To compare your border to another border pattern, use the identity test operator (is). Alternatively, you can use the equality test operator (==) to directly compare your border against a known numeric value. Additionally, you can check if the border contains a given side using the membership test operator (in):

>>> border is Border.TOP | Border.BOTTOM | Border.RIGHT | Border.LEFT

True

>>> border is Border.TOP

False

>>> border == 15

True

>>> border == 16

False

>>> Border.TOP in border

True

Comparing an instance of enum.IntFlag to a number is possible because the flag is a subclass of the built-in integer type, just like enum.IntEnum, which you used before.

Go ahead and add a few convenience properties to your enumeration so that you can detect corners, dead ends, and intersections:

# models/border.py

from enum import IntFlag, auto

class Border(IntFlag):

EMPTY = 0

TOP = auto()

BOTTOM = auto()

LEFT = auto()

RIGHT = auto()

@property

def corner(self) -> bool:

return self in (

self.TOP | self.LEFT,

self.TOP | self.RIGHT,

self.BOTTOM | self.LEFT,

self.BOTTOM | self.RIGHT,

)

@property

def dead_end(self) -> bool:

return self.bit_count() == 3

@property

def intersection(self) -> bool:

return self.bit_count() < 2

All three properties return a Boolean value. In the .corner property, you use the membership test operator (in) to check if an instance of the Border enumeration—indicated by self—is one of the predefined corners. The other two properties rely on the integer’s .bit_count() method, which returns the number of ones in the binary representation of your border.

With the Role and Border building blocks in place, you can now tie them together on a higher abstraction level. In the next section, you’ll implement the Square class.

Model the Square

The purpose of a square is to convey information about a particular location in the maze. Therefore, every square should have known coordinates that can determine its position. The square should also have a border pattern that describes the maze structure at that location. Depending on the purpose of the square, it may optionally play a special role—for example, by indicating the maze entrance.

You’ve already done the hard work by offloading most of these responsibilities to helper classes. The only remaining task is to combine them into a final square object. Open the square module and paste the following code:

# models/square.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

from maze_solver.models.border import Border

from maze_solver.models.role import Role

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Square:

index: int

row: int

column: int

border: Border

role: Role = Role.NONE

You’re using Python’s data class to generate the mundane code for you, which will correctly initialize instances of this class, among a few other things. Enabling the frozen parameter ensures that square objects become immutable after you create them. There’s no point in changing the values of the instance variables once they’re set.

Note: Preferring immutable objects over mutable ones where possible is considered a good programming practice, which can prevent subtle bugs caused by unexpected changes in data.

Notice that, in addition to storing the square’s row and column indices, you also keep track of its one-dimensional index within a flat sequence of squares. This way, the search algorithm can uniquely identify squares. While you could theoretically infer the index from the row and column, you’d also need to know the width and height of the maze, which are none of the square’s business. A little redundancy can sometimes keep data encapsulated.

When creating your Square instance, you must specify its index, row, column, and border pattern, but the role is completely optional. If you skip the role in the initializer, then the square will assume Role.NONE by default.

That’s it! You’ve successfully modeled the Square data type, so all the building blocks are now in place to build the maze.

Build the Maze

At the very core, a maze is an ordered collection of squares, which you can represent with a Python tuple. However, you’ll eventually want to augment your maze model with additional properties and methods, so it makes sense to wrap the sequence of squares in a custom class right away. Type the following code in your maze module:

# models/maze.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

from maze_solver.models.square import Square

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Maze:

squares: tuple[Square, ...]

Here, you use an immutable data class again to ensure that the underlying tuple of Square objects remains unchanged once assigned. You might be inclined to use a Python list instead of a tuple to keep your squares, but that would prevent you from caching partial results of your computations later. Python’s cache requires memoized function arguments to be hashable and, therefore, immutable.

To avoid the extra work when looping over the squares or when accessing one of them by index, you can make your class iterable and subscriptable by implementing these two special methods:

# models/maze.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

from typing import Iterator

from maze_solver.models.square import Square

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Maze:

squares: tuple[Square, ...]

def __iter__(self) -> Iterator[Square]:

return iter(self.squares)

def __getitem__(self, index: int) -> Square:

return self.squares[index]

The first one lets the Maze instances cooperate with the for loop, while the second one enables the square bracket notation for getting squares by index.

Next, you might want to calculate the width and height of the maze, knowing the column and row indices of the underlying squares:

# models/maze.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

from functools import cached_property

from typing import Iterator

from maze_solver.models.square import Square

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Maze:

squares: tuple[Square, ...]

def __iter__(self) -> Iterator[Square]:

return iter(self.squares)

def __getitem__(self, index: int) -> Square:

return self.squares[index]

@cached_property

def width(self):

return max(square.column for square in self) + 1

@cached_property

def height(self):

return max(square.row for square in self) + 1

You take advantage of the iterable nature of the maze by iterating over it to find the maximum column and row index of its squares with the help of the max() function. Adding 1 to the highest index accounts for the zero-based numbering of tuple indices.

Because looping is a relatively expensive operation, you cache the returned values with functools.cached_property instead of using the built-in @property decorator. As a result, the width and height are computed only once on demand, while their subsequent invocations will return the cached value.

The benefit of calculating the maze size by hand is data consistency. If you supplied the width and height through two extra parameters in the class, then there would be no guarantee that the rows and columns would match up with the flat index. On the other hand, inferring the size from the squares avoids this potential problem.

Speaking of consistency, you can also include the validation of the maze by looping over it again when it’s created to make sure that its squares have the expected rows and columns with matching indices. To do that, you’ll leverage the special method .__post_init__() to hook into the initialization process of your data class:

# models/maze.py

# ...

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Maze:

squares: tuple[Square, ...]

def __post_init__(self) -> None:

validate_indices(self)

validate_rows_columns(self)

# ...

def validate_indices(maze: Maze) -> None:

assert [square.index for square in maze] == list(

range(len(maze.squares))

), "Wrong square.index"

def validate_rows_columns(maze: Maze) -> None:

for y in range(maze.height):

for x in range(maze.width):

square = maze[y * maze.width + x]

assert square.row == y, "Wrong square.row"

assert square.column == x, "Wrong square.column"

The first function checks whether the .index property of each square fits into a continuous sequence of numbers that enumerates all the squares in the maze. The second function iterates over the rows and columns in the maze, ensuring that the .row and .column attributes of the corresponding square match up with the current row and column of the loops.

Note: Watch out for the proper indentation of these functions, as they don’t belong to the class body.

Both validation functions rely on the assert statement to raise the AssertionError and prevent the maze from being created in case of invalid data.

Earlier, you stated that a maze must have an entrance and an exit, so it’s worth confirming that it has both. Go ahead and add two more validation functions:

# models/maze.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

from functools import cached_property

from typing import Iterator

from maze_solver.models.role import Role

from maze_solver.models.square import Square

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Maze:

squares: tuple[Square, ...]

def __post_init__(self) -> None:

validate_indices(self)

validate_rows_columns(self)

validate_entrance(self)

validate_exit(self)

# ...

# ...

def validate_entrance(maze: Maze) -> None:

assert 1 == sum(

1 for square in maze if square.role is Role.ENTRANCE

), "Must be exactly one entrance"

def validate_exit(maze: Maze) -> None:

assert 1 == sum(

1 for square in maze if square.role is Role.EXIT

), "Must be exactly one exit"

These count the number of squares whose role is either ENTRANCE or EXIT and verify that there’s exactly one of each. For your convenience, you might as well implement the relevant properties that’ll return the squares with those special roles:

# models/maze.py

# ...

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Maze:

squares: tuple[Square, ...]

# ...

@cached_property

def entrance(self) -> Square:

return next(sq for sq in self if sq.role is Role.ENTRANCE)

@cached_property

def exit(self) -> Square:

return next(sq for sq in self if sq.role is Role.EXIT)

# ...

The code above calls next() on a generator expression that filters the squares by their role. Because you already validated them, you can safely assume that the appropriate squares exist in the maze, and next() won’t raise any exception.

Okay, you can finally build your first maze using the building blocks defined earlier:

>>> from maze_solver.models.border import Border

>>> from maze_solver.models.maze import Maze

>>> from maze_solver.models.role import Role

>>> from maze_solver.models.square import Square

>>> maze = Maze(

... squares=(

... Square(0, 0, 0, Border.TOP | Border.LEFT),

... Square(1, 0, 1, Border.TOP | Border.RIGHT),

... Square(2, 0, 2, Border.LEFT | Border.RIGHT, Role.EXIT),

... Square(3, 0, 3, Border.TOP | Border.LEFT | Border.RIGHT),

... Square(4, 1, 0, Border.BOTTOM | Border.LEFT | Border.RIGHT),

... Square(5, 1, 1, Border.LEFT | Border.RIGHT),

... Square(6, 1, 2, Border.BOTTOM | Border.LEFT),

... Square(7, 1, 3, Border.RIGHT),

... Square(8, 2, 0, Border.TOP | Border.LEFT, Role.ENTRANCE),

... Square(9, 2, 1, Border.BOTTOM),

... Square(10, 2, 2, Border.TOP | Border.BOTTOM),

... Square(11, 2, 3, Border.BOTTOM | Border.RIGHT),

... )

... )

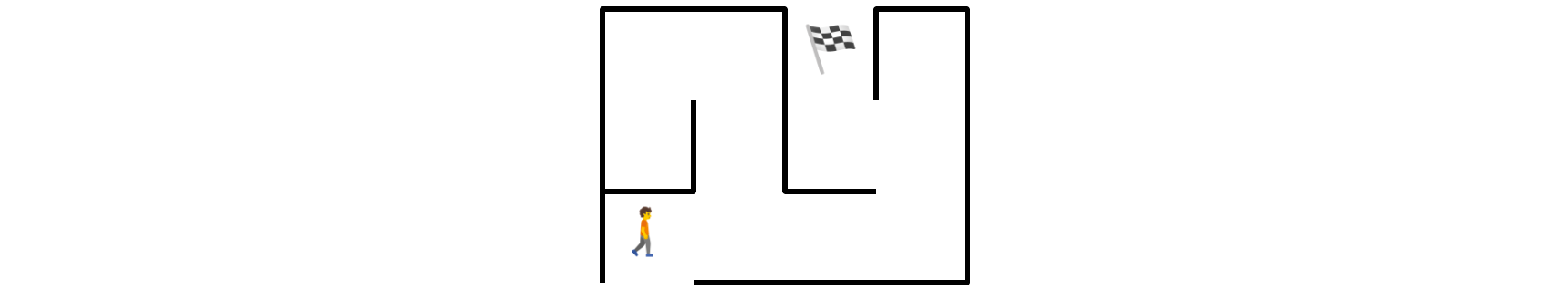

This sample maze has twelve squares, with ten unique border patterns, arranged in three rows and four columns. The entrance to the maze is located in the bottom-left corner, while the exit is in the first row, slightly to the right. The highlighted lines indicate both special squares.

It takes a lot of imagination to visualize the final result just by looking at the code, so this is what your miniature maze will look like:

This may not be a masterpiece yet, but having a small dataset sample to work with is beneficial for several reasons. When something doesn’t work as expected, you’ll be able to spot the problem much quicker. You’ll also have a better understanding of the underlying concepts, allowing you to debug the code more effectively. Finally, because there’s little data to process, you’ll spend less time waiting for the results in your development cycle.

In this step, you identified the building blocks of the maze and implemented them in Python. Now that you can build a maze, the next step for you will be to figure out how to display the maze in a graphical form like the one depicted above.

Step 3: Visualize the Maze With Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG)

If you tried printing a crude visualization of your maze in the console using ASCII characters, then you might have noticed that it doesn’t look all that great. The reason is that, unlike squares, font glyphs are rectangular, which results in a vertically stretched image that doesn’t have the right proportions. Therefore, you need to find a different way to visualize your maze.

By the end of this step, you’ll be able to render any maze and, optionally, one of its solutions using the XML-based scalable vector graphics (SVG) format. You can use your web browser to preview the resulting SVG image, or you can open it in a vector graphics editor like Inkscape.

Model the Maze Solution

Drawing the maze can be fun on its own. However, your end goal is to solve even the most complex maze and render the shortest path from its entrance, through the corridors, to the maze exit. Finding the solution by eyeballing the maze may not always be feasible, but it should be a piece of cake for a computer program.

Add yet another module to your models package, where you’ll define a class to represent the maze solution in an object-oriented way:

maze-solver/

│

├── src/

│ │

│ └── maze_solver/

│ │

│ ├── models/

│ │ ├── __init__.py

│ │ ├── border.py

│ │ ├── maze.py

│ │ ├── role.py

│ │ ├── solution.py

│ │ └── square.py

│ │

│ └── __init__.py

│

└── pyproject.toml

The solution is a sequence of Square objects, which originates at the maze entrance and ends at the exit. Note, however, that you may jump over a few squares at a time without stepping on each as long as they line up horizontally or vertically. This reflects how you’re going to represent the path through the maze as an ordered collection of nodes in a graph.

You can implement the maze solution using the following class:

# models/solution.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

from maze_solver.models.square import Square

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Solution:

squares: tuple[Square, ...]

Coincidentally, this code resembles your Maze data type, which is also a data class with a .squares attribute defined as a tuple. Unlike in the maze implementation, however, this sequence is one-dimensional instead of representing rows and columns. Because of some similarities, though, you can make the Solution instances iterable and subscriptable, too, by implementing a few special methods:

# models/solution.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

from typing import Iterator

from maze_solver.models.square import Square

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Solution:

squares: tuple[Square, ...]

def __iter__(self) -> Iterator[Square]:

return iter(self.squares)

def __getitem__(self, index: int) -> Square:

return self.squares[index]

def __len__(self) -> int:

return len(self.squares)

Additionally, you add the special method .__len__() to compare the length of a solution against other possible solutions.

To make sure that instances of your Solution class represent actual solutions instead of random locations in the maze, you can add a .__post_init__() method to validate the sequence of squares:

# models/solution.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

from functools import reduce

from typing import Iterator

from maze_solver.models.role import Role

from maze_solver.models.square import Square

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Solution:

squares: tuple[Square, ...]

def __post_init__(self) -> None:

assert self.squares[0].role is Role.ENTRANCE

assert self.squares[-1].role is Role.EXIT

reduce(validate_corridor, self.squares)

def __iter__(self) -> Iterator[Square]:

return iter(self.squares)

def __getitem__(self, index: int) -> Square:

return self.squares[index]

def __len__(self) -> int:

return len(self.squares)

def validate_corridor(current: Square, following: Square) -> Square:

assert any([

current.row == following.row,

current.column == following.column

]), "Squares must lie in the same row or column"

return following

Validation of a solution involves checking that its first square is the maze entrance, the last square is the exit, and every two consecutive squares belong to the same row or column. You can do this by using reduce() to check that each pair of squares align either horizontally or vertically. You call any() to assert that either of the two conditions is true.

Now that you have all the building blocks of the maze and its solution, you can draw them using vector graphics.

Implement Geometric Primitives

Create a new Python package in your project with these three placeholder modules in it:

maze-solver/

│

├── src/

│ │

│ └── maze_solver/

│ │

│ ├── models/

│ │ ├── __init__.py

│ │ ├── border.py

│ │ ├── maze.py

│ │ ├── role.py

│ │ ├── solution.py

│ │ └── square.py

│ │

│ ├── view/

│ │ ├── __init__.py

│ │ ├── decomposer.py

│ │ ├── primitives.py

│ │ └── renderer.py

│ │

│ └── __init__.py

│

└── pyproject.toml

You’ll cover each of these modules in more detail in the next few sections, starting with the geometric primitives in this section. Primitives are the basic shapes—like points, lines, rectangles, or polygons—that you’ll build your maze with. Each primitive has only one responsibility, to draw itself by providing the corresponding XML representation according to SVG semantics.

To help generate SVG elements, you’re going to devise a generic function that’ll spit out an XML tag with the given name, optional value, and zero or more attributes:

# view/primitives.py

def tag(name: str, value: str | None = None, **attributes) -> str:

attrs = "" if not attributes else " " + " ".join(

f'{key.replace("_", "-")}="{value}"'

for key, value in attributes.items()

)

if value is None:

return f"<{name}{attrs} />"

return f"<{name}{attrs}>{value}</{name}>"

Because SVG element attributes, such as stroke-width, can contain hyphens, which aren’t valid in Python names, you’ll automatically replace underscores (_) with hyphens (-) so that you can pass them as function arguments. If an element has no value, then you’ll use the XML self-closing tag (<element />).

Here are a few examples illustrating the use of this function:

>>> from maze_solver.view.primitives import tag

>>> # Element name

>>> tag("svg")

'<svg />'

>>> # Element name and value

>>> tag("svg", "Your web browser doesn't support SVG")

"<svg>Your web browser doesn't support SVG</svg>"

>>> # Element name and attributes (including one with a hyphen)

>>> tag("svg", xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg", stroke_linejoin="round")

'<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" stroke-linejoin="round" />'

>>> # Element name, value, and attributes

>>> tag("svg", "SVG not supported", width="100%", height="100%")

'<svg width="100%" height="100%">SVG not supported</svg>'

>>> # Nested elements

>>> tag("svg", tag("rect", fill="blue"), width="100%")

'<svg width="100%"><rect fill="blue" /></svg>'

The element name is the first and only required parameter of the function. The second parameter is the optional value. Notice that both are positional arguments, while element attributes are variable-length keyword arguments. You can also nest elements by using the output of one call to the function as input for another.

To take advantage of static duck typing, which your type checker tool can leverage, you’ll define a protocol or an interface common to all geometric primitives:

# view/primitives.py

from typing import Protocol

class Primitive(Protocol):

def draw(self, **attributes) -> str:

...

# ...

Because protocols are about the interface rather than implementation, it’s common to find either the pass statement or the ellipsis literal (...) in their method bodies. Both work as a placeholder to silence the Python interpreter, which requires that every block of code starting with a colon must not be empty.

The type checker will consider any class implementing the .draw() method with this signature as a subtype of Primitive, even if they’re unrelated through inheritance. The most basic primitive is a Euclidean point comprising the x and y coordinates:

# view/primitives.py

from typing import NamedTuple, Protocol

class Primitive(Protocol):

def draw(self, **attributes) -> str:

...

class Point(NamedTuple):

x: int

y: int

def draw(self, **attributes) -> str:

return f"{self.x},{self.y}"

def translate(self, x=0, y=0) -> "Point":

return Point(self.x + x, self.y + y)

# ...

The class extends a named tuple but not your Primitive protocol. It’s sufficient that it implements the .draw() method, which returns an SVG point as a Python string, to define a concrete primitive. Later, you’ll need to translate your points in x and y directions, so you also implement a relevant method. Because named tuples are immutable, translating a point creates a brand-new object.

The next most basic primitive is a line segment delimited by starting and ending points:

# view/primitives.py

# ...

class Line(NamedTuple):

start: Point

end: Point

def draw(self, **attributes) -> str:

return tag(

"line",

x1=self.start.x,

y1=self.start.y,

x2=self.end.x,

y2=self.end.y,

**attributes,

)

# ...

This time, the .draw() method returns an SVG line, which is a stand-alone element rather than a value of an attribute.

Two other primitives closely related to a line are SVG polylines and polygons, which extend the idea of a line:

# view/primitives.py

# ...

class Polyline(tuple[Point, ...]):

def draw(self, **attributes) -> str:

points = " ".join(point.draw() for point in self)

return tag("polyline", points=points, **attributes)

class Polygon(tuple[Point, ...]):

def draw(self, **attributes) -> str:

points = " ".join(point.draw() for point in self)

return tag("polygon", points=points, **attributes)

# ...

They’re both tuples of two or more points, which look nearly identical. The difference is that a polygon is closed, meaning it connects the first and last point, while the polyline isn’t, leaving the last point unconnected.

Note: In case you were wondering, the points parameter must be passed as a keyword argument to avoid conflating it with the value positional argument.

Sometimes, it may be more convenient to combine existing lines instead of individual points, especially when they don’t form a continuous polyline. That’s when a DisjointLines primitive comes in handy:

# view/primitives.py

# ...

class DisjointLines(tuple[Line, ...]):

def draw(self, **attributes) -> str:

return "".join(line.draw(**attributes) for line in self)

# ...

Note that this is merely a logical collection of lines and has no SVG equivalent. Other, more specific SVG primitives that you’ll be interested in include a rectangle and a text element:

# view/primitives.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

from typing import NamedTuple, Protocol

# ...

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Rect:

top_left: Point | None = None

def draw(self, **attributes) -> str:

if self.top_left:

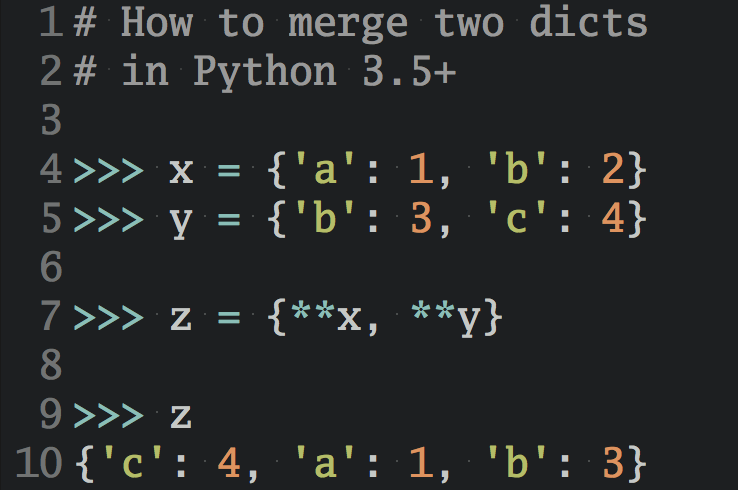

attrs = attributes | {"x": self.top_left.x, "y": self.top_left.y}

else:

attrs = attributes

return tag("rect", **attrs)

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Text:

content: str

point: Point

def draw(self, **attributes) -> str:

return tag(

"text",

self.content,

x=self.point.x,

y=self.point.y,

**attributes

)

# ...

You implement them as data classes rather than tuples or named tuples because they’re not inherently sequences of elements. The rectangle accepts an optional top-left corner, whose coordinates get mixed in with the rest of the attributes through the union operator (|).

Last but not least, you’ll apply the null object pattern again by implementing a dummy NullPrimitive, which returns an empty string:

# view/primitives.py

# ...

class NullPrimitive:

def draw(self, **attributes) -> str:

return ""

# ...

It’ll let you avoid checking for a special case when there are no primitives to represent something in SVG, ultimately leading to cleaner and more readable code.

Next up, you’ll put your primitives to use by decomposing various border patterns around the maze’s squares into SVG elements.

Decompose a Border Into Primitives

Open your decomposer module and type the following function stub at the top of the file, which you’ll continue editing in this section:

# view/decomposer.py

from maze_solver.models.border import Border

from maze_solver.view.primitives import (

Line,

Point,

Primitive,

)

def decompose(border: Border, top_left: Point, square_size: int) -> Primitive:

top_right: Point = top_left.translate(x=square_size)

bottom_right: Point = top_left.translate(x=square_size, y=square_size)

bottom_left: Point = top_left.translate(y=square_size)

top = Line(top_left, top_right)

bottom = Line(bottom_left, bottom_right)

left = Line(top_left, bottom_left)

right = Line(top_right, bottom_right)

The function takes a border pattern, the top-left corner of the corresponding square in SVG coordinates, and the desired square size in SVG coordinates as input. Its goal is to decompose the border into a relevant geometric primitive that you can draw.

First, you locate the other corners of the current square’s border by translating the point that was provided to you as a function parameter. Next, you create the four sides of the border by connecting the corners into lines accordingly. Once you have all the sides and corners, you can construct the polygon, polyline, or lines associated with the given border pattern.

As you may remember, there are sixteen unique patterns, which your function needs to recognize and map to the correct primitives.

There’s only one pattern consisting of all four sides, which you can turn into a polygon:

# view/decomposer.py

from maze_solver.models.border import Border

from maze_solver.view.primitives import (

Line,

Point,

Polygon,

Primitive,

)

def decompose(border: Border, top_left: Point, square_size: int) -> Primitive:

top_right: Point = top_left.translate(x=square_size)

bottom_right: Point = top_left.translate(x=square_size, y=square_size)

bottom_left: Point = top_left.translate(y=square_size)

top = Line(top_left, top_right)

bottom = Line(bottom_left, bottom_right)

left = Line(top_left, bottom_left)

right = Line(top_right, bottom_right)

if border is Border.LEFT | Border.TOP | Border.RIGHT | Border.BOTTOM:

return Polygon(

[

top_left,

top_right,

bottom_right,

bottom_left,

]

)

You compare the square’s border to a predefined pattern to determine whether they match. Next, there are four possible patterns with three sides, which you can describe by the bottom-left-top, left-top-right, top-right-bottom, and right-bottom-left directions:

# view/decomposer.py

from maze_solver.models.border import Border

from maze_solver.view.primitives import (

Line,

Point,

Polygon,

Polyline,

Primitive,

)

def decompose(border: Border, top_left: Point, square_size: int) -> Primitive:

# ...

if border is Border.BOTTOM | Border.LEFT | Border.TOP:

return Polyline(

[

bottom_right,

bottom_left,

top_left,

top_right,

]

)

if border is Border.LEFT | Border.TOP | Border.RIGHT:

return Polyline(

[

bottom_left,

top_left,

top_right,

bottom_right,

]

)

if border is Border.TOP | Border.RIGHT | Border.BOTTOM:

return Polyline(

[

top_left,

top_right,

bottom_right,

bottom_left,

]

)

if border is Border.RIGHT | Border.BOTTOM | Border.LEFT:

return Polyline(

[

top_right,

bottom_right,

bottom_left,

top_left,

]

)

You return a polyline, leaving one missing side in each case. Then, there are six border patterns with two sides, including four patterns—left-top, top-right, bottom-left, and right-bottom—which also form a polyline:

# view/decomposer.py

# ...

def decompose(border: Border, top_left: Point, square_size: int) -> Primitive:

# ...

if border is Border.LEFT | Border.TOP:

return Polyline(

[

bottom_left,

top_left,

top_right,

]

)

if border is Border.TOP | Border.RIGHT:

return Polyline(

[

top_left,

top_right,

bottom_right,

]

)

if border is Border.BOTTOM | Border.LEFT:

return Polyline(

[

bottom_right,

bottom_left,

top_left,

]

)

if border is Border.RIGHT | Border.BOTTOM:

return Polyline(

[

top_right,

bottom_right,

bottom_left,

]

)

The two remaining two-sided patterns, left-right and top-bottom, must be represented as two disjoint lines, which run in parallel:

# view/decomposer.py

from maze_solver.models.border import Border

from maze_solver.view.primitives import (

DisjointLines,

Line,

Point,

Polygon,

Polyline

Primitive,

)

def decompose(border: Border, top_left: Point, square_size: int) -> Primitive:

# ...

if border is Border.LEFT | Border.RIGHT:

return DisjointLines([left, right])

if border is Border.TOP | Border.BOTTOM:

return DisjointLines([top, bottom])

Next, you have four patterns with only one side for each compass direction:

# view/decomposer.py

# ...

def decompose(border: Border, top_left: Point, square_size: int) -> Primitive:

# ...

if border is Border.TOP:

return top

if border is Border.RIGHT:

return right

if border is Border.BOTTOM:

return bottom

if border is Border.LEFT:

return left

Notice that you return the lines you created at the very beginning of the function. Finally, there’s the only case of an empty border pattern without any visual representation, which you can map to the null object primitive:

# view/decomposer.py

from maze_solver.models.border import Border

from maze_solver.view.primitives import (

DisjointLines,

Line,

NullPrimitive,

Point,

Polygon,

Polyline

Primitive,

)

def decompose(border: Border, top_left: Point, square_size: int) -> Primitive:

# ...

return NullPrimitive()

Whew, that was a lot to take in! Now that the hard work is done, you can put the pieces together to achieve some tangible results. It’s time to build the scalable vector graphics renderer.

Build the SVG Renderer

Your scalable vector graphics renderer will take the square size and line width in pixel coordinates as input parameters. At the same time, it’ll assume sensible defaults so that you don’t have to fiddle with numbers to get started:

# view/renderer.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class SVGRenderer:

square_size: int = 100

line_width: int = 6

@property

def offset(self):

return self.line_width // 2

The offset is the distance from the top and left edge of the drawing space, which takes your line width into account. Without it, a line starting at the top-left corner would be drawn at the very edge of the canvas and partially out of view.

The renderer returns a lightweight SVG object, which wraps the textual XML content:

# view/renderer.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

from maze_solver.models.maze import Maze

from maze_solver.models.solution import Solution

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class SVG:

xml_content: str

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class SVGRenderer:

square_size: int = 100

line_width: int = 6

@property

def offset(self):

return self.line_width // 2

def render(self, maze: Maze, solution: Solution | None = None) -> SVG:

...

Later, you’ll add code in the SVG wrapper class to allow for viewing the rendered maze in your web browser. Rendering an SVG image boils down to decomposing the maze and its optional solution into geometric primitives, which you turn into XML tags mashed together into a string:

# view/renderer.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

from maze_solver.models.maze import Maze

from maze_solver.models.solution import Solution

from maze_solver.view.primitives import tag

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class SVG:

xml_content: str

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class SVGRenderer:

square_size: int = 100

line_width: int = 6

@property

def offset(self):

return self.line_width // 2

def render(self, maze: Maze, solution: Solution | None = None) -> SVG:

margins = 2 * (self.offset + self.line_width)

width = margins + maze.width * self.square_size

height = margins + maze.height * self.square_size

return SVG(

tag(

"svg",

self._get_body(maze, solution),

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg",

stroke_linejoin="round",

width=width,

height=height,

viewBox=f"0 0 {width} {height}",

)

)

You calculate the SVG dimensions based on the size of your maze and its squares, and you set the viewBox attribute accordingly. You then call a helper method to get the body of the <svg> tag, which in turn calls four other methods that you’ll implement shortly:

# view/renderer.py

# ...

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class SVGRenderer:

# ...

def _get_body(self, maze: Maze, solution: Solution | None) -> str:

return "".join([

arrow_marker(),

background(),

*map(self._draw_square, maze),

self._draw_solution(solution) if solution else "",

])

The body of your SVG consists of a marker definition, which you’ll use to end the line representing the solution with an arrow pointing to the exit. This definition is followed by a rectangle occupying the entire view to provide a white background. Next, you render the individual squares and overlay them with the solution if supplied.

Fill the SVG Body

To get the arrow marker and the background tags, you call these two top-level functions defined at the bottom of your module:

# view/renderer.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

from maze_solver.models.maze import Maze

from maze_solver.models.solution import Solution

from maze_solver.view.primitives import Rect, tag

# ...

def arrow_marker() -> str:

return tag(

"defs",

tag(

"marker",

tag(

"path",

d="M 0,0 L 10,5 L 0,10 2,5 z",

fill="red",

fill_opacity="50%"

),

id="arrow",

viewBox="0 0 20 20",

refX="2",

refY="5",

markerUnits="strokeWidth",

markerWidth="10",

markerHeight="10",

orient="auto"

)

)

def background() -> str:

return Rect().draw(width="100%", height="100%", fill="white")

The <defs> and <marker> elements define an arrow shape that you’ll reference later in the SVG document. The other function uses your Rect primitive to draw a white rectangle stretched across the entire image.

Before drawing one of the maze’s squares, you need to establish where it should go by transforming its row and column into pixel coordinates:

# view/renderer.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

from maze_solver.models.maze import Maze

from maze_solver.models.solution import Solution

from maze_solver.models.square import Square

from maze_solver.view.primitives import Point, Rect, tag

# ...

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class SVGRenderer:

# ...

def _transform(self, square: Square, extra_offset: int = 0) -> Point:

return Point(

x=square.column * self.square_size,

y=square.row * self.square_size,

).translate(

x=self.offset + extra_offset,

y=self.offset + extra_offset

)

# ...

You scale and translate the square’s coordinates using the desired square size and offset. The resulting point is the top-left corner of your square in the SVG pixel space.

Next, you can start drawing your square, which will involve drawing a border around it, filling it with a color depending on the square type, and putting an optional label icon inside. Each of these elements will become a separate SVG tag that you’ll append to a Python list before joining together.

After transforming the coordinates, you’ll call the function that you defined in the previous section to decompose a border pattern into a drawable primitive:

# view/renderer.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

from maze_solver.models.maze import Maze

from maze_solver.models.solution import Solution

from maze_solver.models.square import Square

from maze_solver.view.decomposer import decompose

from maze_solver.view.primitives import Point, Rect, tag

# ...

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class SVGRenderer:

# ...

def _draw_square(self, square: Square) -> str:

top_left: Point = self._transform(square)

tags = []

tags.append(self._draw_border(square, top_left))

return "".join(tags)

def _draw_border(self, square: Square, top_left: Point) -> str:

return decompose(square.border, top_left, self.square_size).draw(

stroke_width=self.line_width,

stroke="black",

fill="none"

)

# ...

# ...

You draw the border around the given square in the specified pixel location by getting its geometric representation first. This is where the null object pattern shows its strength by letting you treat all border patterns in the same way, even when they don’t have any visual representation.

Note that you created a list of tags that you’ll fill with other elements associated with the same square. Apart from the border, the walls and exterior can have a background, while squares with special roles will have an extra icon inside them:

1# view/renderer.py

2

3from dataclasses import dataclass

4

5from maze_solver.models.maze import Maze

6from maze_solver.models.role import Role

7from maze_solver.models.solution import Solution

8from maze_solver.models.square import Square

9from maze_solver.view.decomposer import decompose

10from maze_solver.view.primitives import Point, Rect, Text, tag

11

12ROLE_EMOJI = {

13 Role.ENTRANCE: "\N{pedestrian}",

14 Role.EXIT: "\N{chequered flag}",

15 Role.ENEMY: "\N{ghost}",

16 Role.REWARD: "\N{white medium star}",

17}

18

19# ...

20

21@dataclass(frozen=True)

22class SVGRenderer:

23 # ...

24

25 def _draw_square(self, square: Square) -> str:

26 top_left: Point = self._transform(square)

27 tags = []

28 if square.role is Role.EXTERIOR:

29 tags.append(exterior(top_left, self.square_size, self.line_width))

30 elif square.role is Role.WALL:

31 tags.append(wall(top_left, self.square_size, self.line_width))

32 elif emoji := ROLE_EMOJI.get(square.role):

33 tags.append(label(emoji, top_left, self.square_size // 2))

34 tags.append(self._draw_border(square, top_left))

35 return "".join(tags)

36

37 # ...

38

39# ...

40

41def exterior(top_left: Point, size: int, line_width: int) -> str:

42 return Rect(top_left).draw(

43 width=size,

44 height=size,

45 stroke_width=line_width,

46 stroke="none",

47 fill="white"

48 )

49

50def wall(top_left: Point, size: int, line_width: int) -> str:

51 return Rect(top_left).draw(

52 width=size,

53 height=size,

54 stroke_width=line_width,

55 stroke="none",

56 fill="lightgray"

57 )

58

59def label(emoji: str, top_left: Point, offset: int) -> str:

60 return Text(emoji, top_left.translate(x=offset, y=offset)).draw(

61 font_size=f"{offset}px",

62 text_anchor="middle",

63 dominant_baseline="middle"

64 )

Here’s what the highlighted lines do:

- Lines 12 to 17 define a mapping of a subset of

Rolemembers to emoji icons expressed with Unicode name aliases. - Lines 28 to 33 call one of the helper functions defined below to draw the square’s background or an icon, depending on the square’s role.

- Lines 41 to 57 define functions that draw a rectangle with either white or light gray background.

- Lines 59 to 64 define a function that draws the specified emoji icon in the middle of the square.

Finally, the last missing method in the SVGRenderer class is one that draws the solution as a line ending with an arrow marker:

# view/renderer.py

from dataclasses import dataclass

from maze_solver.models.maze import Maze

from maze_solver.models.role import Role

from maze_solver.models.solution import Solution

from maze_solver.models.square import Square

from maze_solver.view.decomposer import decompose

from maze_solver.view.primitives import Point, Polyline, Rect, Text, tag

# ...

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class SVGRenderer:

# ...

def _draw_solution(self, solution: Solution) -> str:

return Polyline(

[

self._transform(point, self.square_size // 2)

for point in solution

]

).draw(

stroke_width=self.line_width * 2,

stroke_opacity="50%",

stroke="red",

fill="none",

marker_end="url(#arrow)"

)

# ...

# ...

You transform the squares of the solution to get their corresponding pixel coordinates. Notice that you add an extra offset to center the solution’s line vertically and horizontally in each square. The marker-end SVG attribute refers to the SVG object identified as #arrow, which you defined earlier.

At this point, you can print the resulting SVG in the console or save its XML content to a local file:

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> from maze_solver.models.border import Border

>>> from maze_solver.models.maze import Maze

>>> from maze_solver.models.role import Role

>>> from maze_solver.models.solution import Solution

>>> from maze_solver.models.square import Square

>>> from maze_solver.view.renderer import SVGRenderer

>>> maze = Maze(

... squares=(

... Square(0, 0, 0, Border.TOP | Border.LEFT),

... Square(1, 0, 1, Border.TOP | Border.RIGHT),

... Square(2, 0, 2, Border.LEFT | Border.RIGHT, Role.EXIT),

... Square(3, 0, 3, Border.TOP | Border.LEFT | Border.RIGHT),

... Square(4, 1, 0, Border.BOTTOM | Border.LEFT | Border.RIGHT),

... Square(5, 1, 1, Border.LEFT | Border.RIGHT),

... Square(6, 1, 2, Border.BOTTOM | Border.LEFT),

... Square(7, 1, 3, Border.RIGHT),

... Square(8, 2, 0, Border.TOP | Border.LEFT, Role.ENTRANCE),

... Square(9, 2, 1, Border.BOTTOM),

... Square(10, 2, 2, Border.TOP | Border.BOTTOM),

... Square(11, 2, 3, Border.BOTTOM | Border.RIGHT),

... )

... )

>>> solution = Solution(squares=tuple(maze[i] for i in (8, 11, 7, 6, 2)))

>>> svg = SVGRenderer().render(maze, solution)

>>> with Path("maze.svg").open(mode="w", encoding="utf-8") as file:

... file.write(svg.xml_content)

...

This will save the rendered maze and your manually built solution in a file named maze.svg, which you can open using an external editor or viewer. However, it would be much more convenient to have a .preview() method on the SVG instance that you could call directly to have the image displayed to you. You’ll implement that method now.

Preview the Rendered Maze and Its Solution

These days, modern web browsers support scalable vector graphics out of the box, making them ideal SVG viewers. Websites embed SVG elements within their HTML content, style them using CSS, and even animate and interact with them dynamically through JavaScript. You’ll leverage some of these features to show your rendered SVG image using Python.

Head over to the renderer module again and add an .html_content property in your SVG class:

# view/renderer.py

import textwrap

from dataclasses import dataclass

from maze_solver.models.maze import Maze

from maze_solver.models.role import Role

from maze_solver.models.solution import Solution

from maze_solver.models.square import Square

from maze_solver.view.decomposer import decompose

from maze_solver.view.primitives import Point, Polyline, Rect, Text, tag

# ...

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class SVG:

xml_content: str

@property

def html_content(self) -> str:

return textwrap.dedent("""\

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

<title>SVG Preview</title>

</head>

<body>

{0}

</body>

</html>""").format(self.xml_content)

# ...

This property returns a minimal HTML5 website with your rendered SVG image in its body. You use textwrap.dedent() to remove the leading whitespace from each line of your HTML template and replace the {0} placeholder with the object’s .xml_content attribute. Note that, in this case, using the str.format() method is preferable over an f-string literal, which would affect the indentation of the lines in an undesirable way.

This is what the output will look like when you print it against a sample SVG instance:

>>> from maze_solver.view.renderer import SVG

>>> svg = SVG('<svg><rect width="30" height="20" fill="red" /></svg>')

>>> print(svg.html_content)

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

<title>SVG Preview</title>

</head>

<body>

<svg><rect width="30" height="20" fill="red" /></svg>

</body>

</html>

If you save this piece of HTML in a file and open it with your web browser, then you’ll see a small red rectangle in the top-left corner. However, you can automate these steps using a few modules in Python’s standard library.

Define the .preview() method in your class, which will save the HTML to a temporary file and open it using your web browser:

# view/renderer.py

import tempfile

import textwrap

import webbrowser

from dataclasses import dataclass

from maze_solver.models.maze import Maze

from maze_solver.models.role import Role

from maze_solver.models.solution import Solution

from maze_solver.models.square import Square

from maze_solver.view.decomposer import decompose

from maze_solver.view.primitives import Point, Polyline, Rect, Text, tag

# ...

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class SVG:

xml_content: str

@property

def html_content(self) -> str:

return textwrap.dedent("""\

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

<title>SVG Preview</title>

</head>

<body>

{0}

</body>

</html>""").format(self.xml_content)

def preview(self) -> None:

with tempfile.NamedTemporaryFile(

mode="w", encoding="utf-8", suffix=".html", delete=False

) as file:

file.write(self.html_content)

webbrowser.open(f"file://{file.name}")

# ...

You create a named temporary file with the .html suffix so that your web browser can recognize it correctly. Note that you also set the delete=False flag to prevent Python from automatically deleting that file before you have a chance to load it in the first place. Next, you display the rendered SVG image in your default web browser using the webbrowser module.

Note: Make sure to put the last line of code in the .preview() method outside of the with statement’s block. Because temporary files are always buffered in the text mode, calling .write() may not immediately flush pending data onto the physical disk. Only when you manually close the file or have the with statement do it for you at the end of the block will the temporary file be written to disk.

Now, try this code snippet in your Python REPL:

>>> from maze_solver.models.border import Border

>>> from maze_solver.models.maze import Maze

>>> from maze_solver.models.role import Role

>>> from maze_solver.models.solution import Solution

>>> from maze_solver.models.square import Square

>>> from maze_solver.view.renderer import SVGRenderer

>>> maze = Maze(

... squares=(

... Square(0, 0, 0, Border.TOP | Border.LEFT),

... Square(1, 0, 1, Border.TOP | Border.RIGHT),

... Square(2, 0, 2, Border.LEFT | Border.RIGHT, Role.EXIT),

... Square(3, 0, 3, Border.TOP | Border.LEFT | Border.RIGHT),

... Square(4, 1, 0, Border.BOTTOM | Border.LEFT | Border.RIGHT),

... Square(5, 1, 1, Border.LEFT | Border.RIGHT),

... Square(6, 1, 2, Border.BOTTOM | Border.LEFT),

... Square(7, 1, 3, Border.RIGHT),

... Square(8, 2, 0, Border.TOP | Border.LEFT, Role.ENTRANCE),

... Square(9, 2, 1, Border.BOTTOM),

... Square(10, 2, 2, Border.TOP | Border.BOTTOM),

... Square(11, 2, 3, Border.BOTTOM | Border.RIGHT),

... )

... )

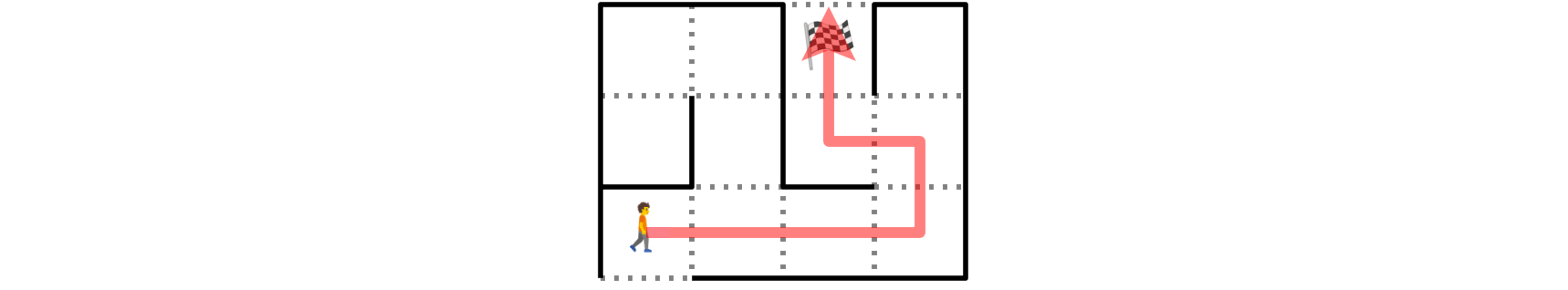

>>> solution = Solution(squares=[maze[i] for i in (8, 11, 7, 6, 2)])

>>> renderer = SVGRenderer()

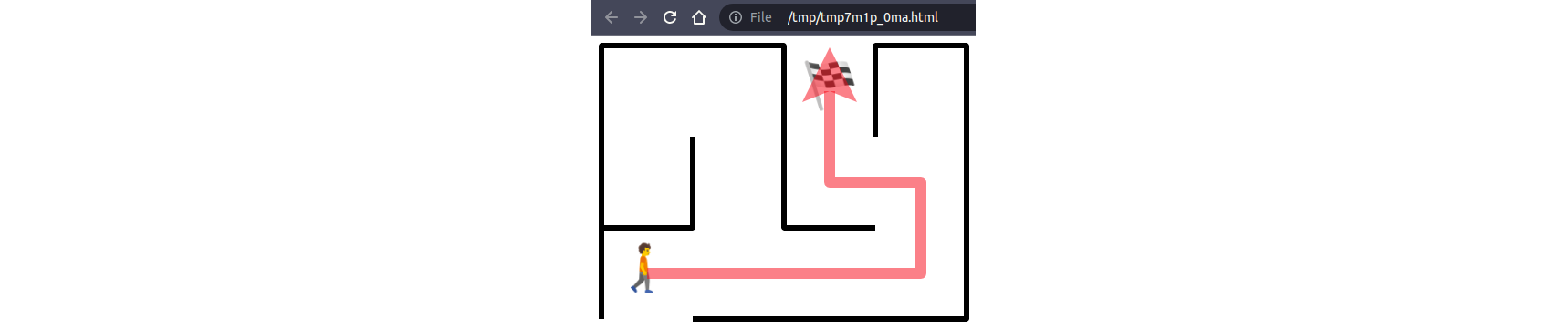

>>> renderer.render(maze).preview()

>>> renderer.render(maze, solution).preview()

Isn’t it more convenient than manually writing the rendered solution each time and trying to find the resulting file with your file manager? Notice how the .preview() method lets you choose between showing the solution or not. The maze with its solution rendered in your web browser should look like this: