Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Parallel Iteration With Python's zip() Function

Python’s zip() function creates an iterator that will aggregate elements from two or more iterables. You can use the resulting iterator to quickly and consistently solve common programming problems, like creating dictionaries. In this tutorial, you’ll discover the logic behind the Python zip() function and how you can use it to solve real-world problems.

By the end of this tutorial, you’ll learn:

- How

zip()works in both Python 3 and Python 2 - How to use the Python

zip()function for parallel iteration - How to create dictionaries on the fly using

zip()

Free Bonus: 5 Thoughts On Python Mastery, a free course for Python developers that shows you the roadmap and the mindset you’ll need to take your Python skills to the next level.

Understanding the Python zip() Function

zip() is available in the built-in namespace. If you use dir() to inspect __builtins__, then you’ll see zip() at the end of the list:

>>> dir(__builtins__)

['ArithmeticError', 'AssertionError', 'AttributeError', ..., 'zip']

You can see that 'zip' is the last entry in the list of available objects.

According to the official documentation, Python’s zip() function behaves as follows:

Returns an iterator of tuples, where the i-th tuple contains the i-th element from each of the argument sequences or iterables. The iterator stops when the shortest input iterable is exhausted. With a single iterable argument, it returns an iterator of 1-tuples. With no arguments, it returns an empty iterator. (Source)

You’ll unpack this definition throughout the rest of the tutorial. As you work through the code examples, you’ll see that Python zip operations work just like the physical zipper on a bag or pair of jeans. Interlocking pairs of teeth on both sides of the zipper are pulled together to close an opening. In fact, this visual analogy is perfect for understanding zip(), since the function was named after physical zippers!

Using zip() in Python

Python’s zip() function is defined as zip(*iterables). The function takes in iterables as arguments and returns an iterator. This iterator generates a series of tuples containing elements from each iterable. zip() can accept any type of iterable, such as files, lists, tuples, dictionaries, sets, and so on.

Passing n Arguments

If you use zip() with n arguments, then the function will return an iterator that generates tuples of length n. To see this in action, take a look at the following code block:

>>> numbers = [1, 2, 3]

>>> letters = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> zipped = zip(numbers, letters)

>>> zipped # Holds an iterator object

<zip object at 0x7fa4831153c8>

>>> type(zipped)

<class 'zip'>

>>> list(zipped)

[(1, 'a'), (2, 'b'), (3, 'c')]

Here, you use zip(numbers, letters) to create an iterator that produces tuples of the form (x, y). In this case, the x values are taken from numbers and the y values are taken from letters. Notice how the Python zip() function returns an iterator. To retrieve the final list object, you need to use list() to consume the iterator.

If you’re working with sequences like lists, tuples, or strings, then your iterables are guaranteed to be evaluated from left to right. This means that the resulting list of tuples will take the form [(numbers[0], letters[0]), (numbers[1], letters[1]),..., (numbers[n], letters[n])]. However, for other types of iterables (like sets), you might see some weird results:

>>> s1 = {2, 3, 1}

>>> s2 = {'b', 'a', 'c'}

>>> list(zip(s1, s2))

[(1, 'a'), (2, 'c'), (3, 'b')]

In this example, s1 and s2 are set objects, which don’t keep their elements in any particular order. This means that the tuples returned by zip() will have elements that are paired up randomly. If you’re going to use the Python zip() function with unordered iterables like sets, then this is something to keep in mind.

Passing No Arguments

You can call zip() with no arguments as well. In this case, you’ll simply get an empty iterator:

>>> zipped = zip()

>>> zipped

<zip object at 0x7f196294a488>

>>> list(zipped)

[]

Here, you call zip() with no arguments, so your zipped variable holds an empty iterator. If you consume the iterator with list(), then you’ll see an empty list as well.

You could also try to force the empty iterator to yield an element directly. In this case, you’ll get a StopIteration exception:

>>> zipped = zip()

>>> next(zipped)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

StopIteration

When you call next() on zipped, Python tries to retrieve the next item. However, since zipped holds an empty iterator, there’s nothing to pull out, so Python raises a StopIteration exception.

Passing One Argument

Python’s zip() function can take just one argument as well. The result will be an iterator that yields a series of 1-item tuples:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> zipped = zip(a)

>>> list(zipped)

[(1,), (2,), (3,)]

This may not be that useful, but it still works. Perhaps you can find some use cases for this behavior of zip()!

As you can see, you can call the Python zip() function with as many input iterables as you need. The length of the resulting tuples will always equal the number of iterables you pass as arguments. Here’s an example with three iterables:

>>> integers = [1, 2, 3]

>>> letters = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> floats = [4.0, 5.0, 6.0]

>>> zipped = zip(integers, letters, floats) # Three input iterables

>>> list(zipped)

[(1, 'a', 4.0), (2, 'b', 5.0), (3, 'c', 6.0)]

Here, you call the Python zip() function with three iterables, so the resulting tuples have three elements each.

Passing Arguments of Unequal Length

When you’re working with the Python zip() function, it’s important to pay attention to the length of your iterables. It’s possible that the iterables you pass in as arguments aren’t the same length.

In these cases, the number of elements that zip() puts out will be equal to the length of the shortest iterable. The remaining elements in any longer iterables will be totally ignored by zip(), as you can see here:

>>> list(zip(range(5), range(100)))

[(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, 2), (3, 3), (4, 4)]

Since 5 is the length of the first (and shortest) range() object, zip() outputs a list of five tuples. There are still 95 unmatched elements from the second range() object. These are all ignored by zip() since there are no more elements from the first range() object to complete the pairs.

If trailing or unmatched values are important to you, then you can use itertools.zip_longest() instead of zip(). With this function, the missing values will be replaced with whatever you pass to the fillvalue argument (defaults to None). The iteration will continue until the longest iterable is exhausted:

>>> from itertools import zip_longest

>>> numbers = [1, 2, 3]

>>> letters = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> longest = range(5)

>>> zipped = zip_longest(numbers, letters, longest, fillvalue='?')

>>> list(zipped)

[(1, 'a', 0), (2, 'b', 1), (3, 'c', 2), ('?', '?', 3), ('?', '?', 4)]

Here, you use itertools.zip_longest() to yield five tuples with elements from letters, numbers, and longest. The iteration only stops when longest is exhausted. The missing elements from numbers and letters are filled with a question mark ?, which is what you specified with fillvalue.

Since Python 3.10, zip() has a new optional keyword argument called strict, which was introduced through PEP 618—Add Optional Length-Checking To zip. This argument’s main goal is to provide a safe way to handle iterables of unequal length.

The default value of strict is False, which ensures that zip() remains backward compatible and has a default behavior that matches its behavior in older Python 3 versions:

>>> # Python >= 3.10

>>> list(zip(range(5), range(100)))

[(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, 2), (3, 3), (4, 4)]

In Python >= 3.10, calling zip() without altering the default value to strict still gives you a list of five tuples, with the unmatched elements from the second range() object ignored.

Alternatively, if you set strict to True, then zip() checks if the input iterables you provided as arguments have the same length, raising a ValueError if they don’t:

>>> # Python >= 3.10

>>> list(zip(range(5), range(100), strict=True))

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ValueError: zip() argument 2 is longer than argument 1

This new feature of zip() is useful when you need to make sure that the function only accepts iterables of equal length. Setting strict to True makes code that expects equal-length iterables safer, ensuring that faulty changes to the caller code don’t result in silently losing data.

Comparing zip() in Python 3 and 2

Python’s zip() function works differently in both versions of the language. In Python 2, zip() returns a list of tuples. The resulting list is truncated to the length of the shortest input iterable. If you call zip() with no arguments, then you get an empty list in return:

>>> # Python 2

>>> zipped = zip(range(3), 'ABCD')

>>> zipped # Hold a list object

[(0, 'A'), (1, 'B'), (2, 'C')]

>>> type(zipped)

<type 'list'>

>>> zipped = zip() # Create an empty list

>>> zipped

[]

In this case, your call to the Python zip() function returns a list of tuples truncated at the value C. When you call zip() with no arguments, you get an empty list.

In Python 3, however, zip() returns an iterator. This object yields tuples on demand and can be traversed only once. The iteration ends with a StopIteration exception once the shortest input iterable is exhausted. If you supply no arguments to zip(), then the function returns an empty iterator:

>>> # Python 3

>>> zipped = zip(range(3), 'ABCD')

>>> zipped # Hold an iterator

<zip object at 0x7f456ccacbc8>

>>> type(zipped)

<class 'zip'>

>>> list(zipped)

[(0, 'A'), (1, 'B'), (2, 'C')]

>>> zipped = zip() # Create an empty iterator

>>> zipped

<zip object at 0x7f456cc93ac8>

>>> next(zipped)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<input>", line 1, in <module>

next(zipped)

StopIteration

Here, your call to zip() returns an iterator. The first iteration is truncated at C, and the second one results in a StopIteration exception. In Python 3, you can also emulate the Python 2 behavior of zip() by wrapping the returned iterator in a call to list(). This will run through the iterator and return a list of tuples.

If you regularly use Python 2, then note that using zip() with long input iterables can unintentionally consume a lot of memory. In these situations, consider using itertools.izip(*iterables) instead. This function creates an iterator that aggregates elements from each of the iterables. It produces the same effect as zip() in Python 3:

>>> # Python 2

>>> from itertools import izip

>>> zipped = izip(range(3), 'ABCD')

>>> zipped

<itertools.izip object at 0x7f3614b3fdd0>

>>> list(zipped)

[(0, 'A'), (1, 'B'), (2, 'C')]

In this example, you call itertools.izip() to create an iterator. When you consume the returned iterator with list(), you get a list of tuples, just as if you were using zip() in Python 3. The iteration stops when the shortest input iterable is exhausted.

If you really need to write code that behaves the same way in both Python 2 and Python 3, then you can use a trick like the following:

try:

from itertools import izip as zip

except ImportError:

pass

Here, if izip() is available in itertools, then you’ll know that you’re in Python 2 and izip() will be imported using the alias zip. Otherwise, your program will raise an ImportError and you’ll know that you’re in Python 3. (The pass statement here is just a placeholder.)

With this trick, you can safely use the Python zip() function throughout your code. When run, your program will automatically select and use the correct version.

So far, you’ve covered how Python’s zip() function works and learned about some of its most important features. Now it’s time to roll up your sleeves and start coding real-world examples!

Looping Over Multiple Iterables

Looping over multiple iterables is one of the most common use cases for Python’s zip() function. If you need to iterate through multiple lists, tuples, or any other sequence, then it’s likely that you’ll fall back on zip(). This section will show you how to use zip() to iterate through multiple iterables at the same time.

Traversing Lists in Parallel

Python’s zip() function allows you to iterate in parallel over two or more iterables. Since zip() generates tuples, you can unpack these in the header of a for loop:

>>> letters = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> numbers = [0, 1, 2]

>>> for l, n in zip(letters, numbers):

... print(f'Letter: {l}')

... print(f'Number: {n}')

...

Letter: a

Number: 0

Letter: b

Number: 1

Letter: c

Number: 2

Here, you iterate through the series of tuples returned by zip() and unpack the elements into l and n. When you combine zip(), for loops, and tuple unpacking, you can get a useful and Pythonic idiom for traversing two or more iterables at once.

You can also iterate through more than two iterables in a single for loop. Consider the following example, which has three input iterables:

>>> letters = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> numbers = [0, 1, 2]

>>> operators = ['*', '/', '+']

>>> for l, n, o in zip(letters, numbers, operators):

... print(f'Letter: {l}')

... print(f'Number: {n}')

... print(f'Operator: {o}')

...

Letter: a

Number: 0

Operator: *

Letter: b

Number: 1

Operator: /

Letter: c

Number: 2

Operator: +

In this example, you use zip() with three iterables to create and return an iterator that generates 3-item tuples. This lets you iterate through all three iterables in one go. There’s no restriction on the number of iterables you can use with Python’s zip() function.

Note: If you want to dive deeper into Python for loops, check out Python “for” Loops (Definite Iteration).

Traversing Dictionaries in Parallel

In Python 3.6 and beyond, dictionaries are ordered collections, meaning they keep their elements in the same order in which they were introduced. If you take advantage of this feature, then you can use the Python zip() function to iterate through multiple dictionaries in a safe and coherent way:

>>> dict_one = {'name': 'John', 'last_name': 'Doe', 'job': 'Python Consultant'}

>>> dict_two = {'name': 'Jane', 'last_name': 'Doe', 'job': 'Community Manager'}

>>> for (k1, v1), (k2, v2) in zip(dict_one.items(), dict_two.items()):

... print(k1, '->', v1)

... print(k2, '->', v2)

...

name -> John

name -> Jane

last_name -> Doe

last_name -> Doe

job -> Python Consultant

job -> Community Manager

Here, you iterate through dict_one and dict_two in parallel. In this case, zip() generates tuples with the items from both dictionaries. Then, you can unpack each tuple and gain access to the items of both dictionaries at the same time.

Note: If you want to dive deeper into dictionary iteration, check out How to Iterate Through a Dictionary in Python.

Notice that, in the above example, the left-to-right evaluation order is guaranteed. You can also use Python’s zip() function to iterate through sets in parallel. However, you’ll need to consider that, unlike dictionaries in Python 3.6, sets don’t keep their elements in order. If you forget this detail, the final result of your program may not be quite what you want or expect.

Unzipping a Sequence

There’s a question that comes up frequently in forums for new Pythonistas: “If there’s a zip() function, then why is there no unzip() function that does the opposite?”

The reason why there’s no unzip() function in Python is because the opposite of zip() is… well, zip(). Do you recall that the Python zip() function works just like a real zipper? The examples so far have shown you how Python zips things closed. So, how do you unzip Python objects?

Say you have a list of tuples and want to separate the elements of each tuple into independent sequences. To do this, you can use zip() along with the unpacking operator *, like so:

>>> pairs = [(1, 'a'), (2, 'b'), (3, 'c'), (4, 'd')]

>>> numbers, letters = zip(*pairs)

>>> numbers

(1, 2, 3, 4)

>>> letters

('a', 'b', 'c', 'd')

Here, you have a list of tuples containing some kind of mixed data. Then, you use the unpacking operator * to unzip the data, creating two different lists (numbers and letters).

Sorting in Parallel

Sorting is a common operation in programming. Suppose you want to combine two lists and sort them at the same time. To do this, you can use zip() along with .sort() as follows:

>>> letters = ['b', 'a', 'd', 'c']

>>> numbers = [2, 4, 3, 1]

>>> data1 = list(zip(letters, numbers))

>>> data1

[('b', 2), ('a', 4), ('d', 3), ('c', 1)]

>>> data1.sort() # Sort by letters

>>> data1

[('a', 4), ('b', 2), ('c', 1), ('d', 3)]

>>> data2 = list(zip(numbers, letters))

>>> data2

[(2, 'b'), (4, 'a'), (3, 'd'), (1, 'c')]

>>> data2.sort() # Sort by numbers

>>> data2

[(1, 'c'), (2, 'b'), (3, 'd'), (4, 'a')]

In this example, you first combine two lists with zip() and sort them. Notice how data1 is sorted by letters and data2 is sorted by numbers.

You can also use sorted() and zip() together to achieve a similar result:

>>> letters = ['b', 'a', 'd', 'c']

>>> numbers = [2, 4, 3, 1]

>>> data = sorted(zip(letters, numbers)) # Sort by letters

>>> data

[('a', 4), ('b', 2), ('c', 1), ('d', 3)]

In this case, sorted() runs through the iterator generated by zip() and sorts the items by letters, all in one go. This approach can be a little bit faster since you’ll need only two function calls: zip() and sorted().

With sorted(), you’re also writing a more general piece of code. This will allow you to sort any kind of sequence, not just lists.

Calculating in Pairs

You can use the Python zip() function to make some quick calculations. Suppose you have the following data in a spreadsheet:

| Element/Month | January | February | March |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sales | 52,000.00 | 51,000.00 | 48,000.00 |

| Production Cost | 46,800.00 | 45,900.00 | 43,200.00 |

You’re going to use this data to calculate your monthly profit. zip() can provide you with a fast way to make the calculations:

>>> total_sales = [52000.00, 51000.00, 48000.00]

>>> prod_cost = [46800.00, 45900.00, 43200.00]

>>> for sales, costs in zip(total_sales, prod_cost):

... profit = sales - costs

... print(f'Total profit: {profit}')

...

Total profit: 5200.0

Total profit: 5100.0

Total profit: 4800.0

Here, you calculate the profit for each month by subtracting costs from sales. Python’s zip() function combines the right pairs of data to make the calculations. You can generalize this logic to make any kind of complex calculation with the pairs returned by zip().

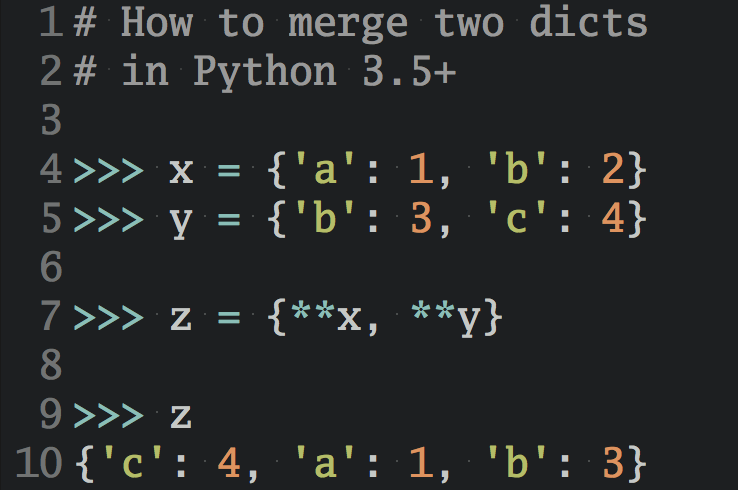

Building Dictionaries

Python’s dictionaries are a very useful data structure. Sometimes, you might need to build a dictionary from two different but closely related sequences. A convenient way to achieve this is to use dict() and zip() together. For example, suppose you retrieved a person’s data from a form or a database. Now you have the following lists of data:

>>> fields = ['name', 'last_name', 'age', 'job']

>>> values = ['John', 'Doe', '45', 'Python Developer']

With this data, you need to create a dictionary for further processing. In this case, you can use dict() along with zip() as follows:

>>> a_dict = dict(zip(fields, values))

>>> a_dict

{'name': 'John', 'last_name': 'Doe', 'age': '45', 'job': 'Python Developer'}

Here, you create a dictionary that combines the two lists. zip(fields, values) returns an iterator that generates 2-items tuples. If you call dict() on that iterator, then you’ll be building the dictionary you need. The elements of fields become the dictionary’s keys, and the elements of values represent the values in the dictionary.

You can also update an existing dictionary by combining zip() with dict.update(). Suppose that John changes his job and you need to update the dictionary. You can do something like the following:

>>> new_job = ['Python Consultant']

>>> field = ['job']

>>> a_dict.update(zip(field, new_job))

>>> a_dict

{'name': 'John', 'last_name': 'Doe', 'age': '45', 'job': 'Python Consultant'}

Here, dict.update() updates the dictionary with the key-value tuple you created using Python’s zip() function. With this technique, you can easily overwrite the value of job.

Conclusion

In this tutorial, you’ve learned how to use Python’s zip() function. zip() can receive multiple iterables as input. It returns an iterator that can generate tuples with paired elements from each argument. The resulting iterator can be quite useful when you need to process multiple iterables in a single loop and perform some actions on their items at the same time.

Now you can:

- Use the

zip()function in both Python 3 and Python 2 - Loop over multiple iterables and perform different actions on their items in parallel

- Create and update dictionaries on the fly by zipping two input iterables together

You’ve also coded a few examples that you can use as a starting point for implementing your own solutions using Python’s zip() function. Feel free to modify these examples as you explore zip() in depth!

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Parallel Iteration With Python's zip() Function